This article was written by Fiona Broom and produced by SciDev.Net’s Global desk. Bothina Osama, Zoraida Patillo, Aleida Rueda, Didier Ladislas Lando and Joel Adriano contributed reporting.

Read the full article on SciDev.Net.

Speed Read

- Food price pain to continue into 2023, food security analysts warn

- Major crop losses expected due to fertiliser shortages, climate, conflict

- Sustainable solutions needed to end ongoing cycle of global food crises

The world is experiencing its third major food crisis this century. Can food systems become more resilient to shocks? Fiona Broom investigates.

Rises in staple food prices around the world are pushing family budgets to breaking point, a SciDev.Net investigation has revealed, as millions of people teeter on the brink of starvation.

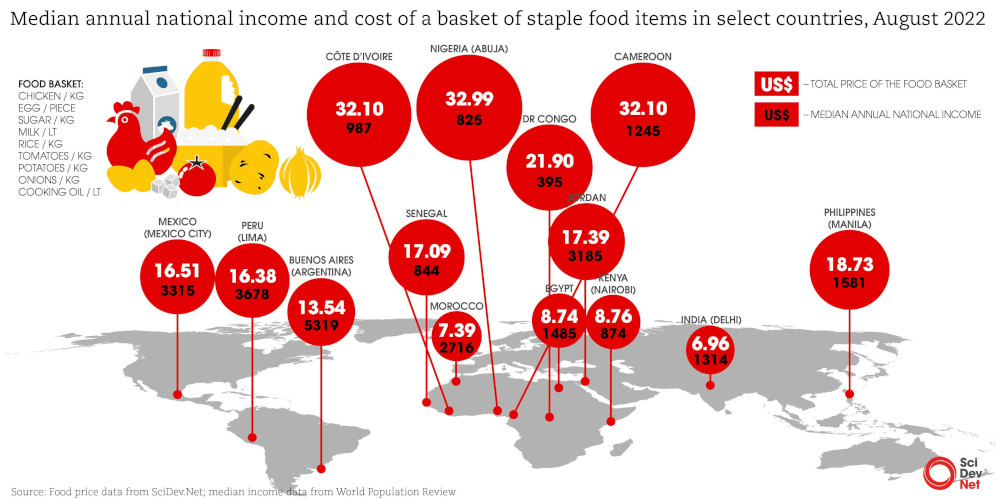

While gathering food price data at markets, supermarkets and independent stores across the global South, SciDev.Net recorded major spikes in everyday staples. When compared against median annual salaries, the cost of a basket of food makes alarming reading.

One year ago, US$150 was enough for Egyptian government employee Abdel Moneim Mahmoud to meet the basic food needs of his family for a month. Now, Mahmoud’s food bill has risen to US$260.

“My monthly income was divided between securing food needs, paying utility bills such as electricity, water and gas, and saving part of it to meet health emergencies and secure school and university expenses for my children,” Mahmoud, 56, tells SciDev.Net.

“But the significant rises in food prices confused the family budget, and one income was no longer sufficient. I had no choice but to look for additional work to meet the monthly obligations.”

The head of the UN’s World Food Programme, David Beasley, says the world faces a looming threat of mass starvation and famine. “We are facing a global emergency of unprecedented magnitude,” he warned, highlighting the combined repercussions of climate change, conflict, and COVID-19.

The world’s most vulnerable communities are experiencing some of the highest food prices this century, and this trend is expected to continue into 2023. Families are being forced to reduce their diets as food price inflation hits household budgets.

Nutrition specialists say they are already seeing the knock-on effect of malnourishment in children, with women and girls particularly at risk. In 2021, at least 150 million more women than men experienced food insecurity and this gap is growing, according to analysis by the humanitarian organisation CARE.

“Some days my husband and I eat just once because we prefer our children don’t go to bed with their stomachs empty. I can’t buy enough food for them at these prices.”

Rosa Márquez, street vendor in Lima

Even before the food crisis hit, the World Bank’s Global Economic Prospects report shows that households in developing countries spent an average 40 per cent of their income on staple foods – while national figures show that food cost families in the United States and the United Kingdom around ten per cent of their budgets. Now the World Bank warns that “stubbornly high” food price inflation in the global South is leaving communities at risk of worsening food insecurity and malnutrition, while “food price surges of the same magnitude have been associated with tens of millions more people falling into extreme poverty in low-income countries”.

What’s driving the crisis?

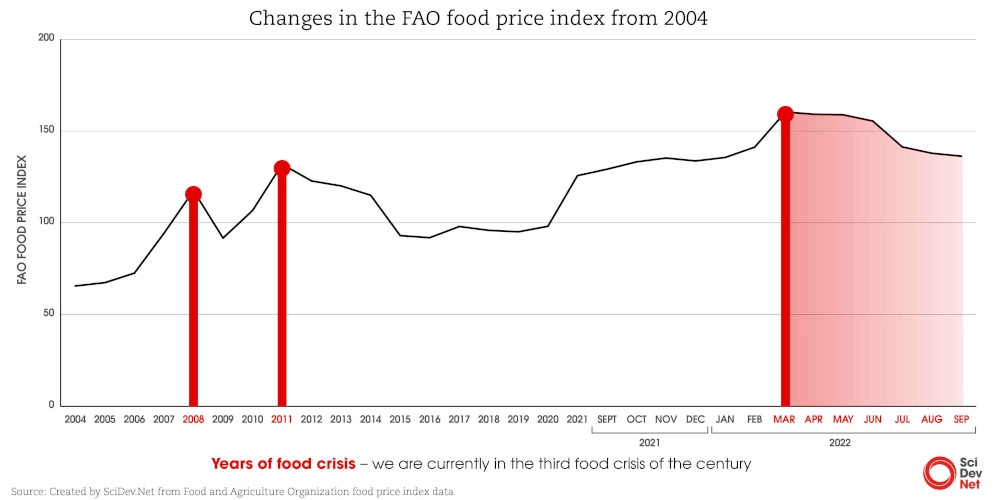

The global financial crisis of 2007-2008 had a major impact on food prices that continues to be felt today. From 2006 to 2008 the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) reported a 60 per cent increase in the world food price index – the FAO’s measure of the monthly change in international prices of a food basket containing meat, dairy, cereals, vegetable oils and sugar.

Similar price volatility was seen in the 2010-2011 crisis – which was fuelled by failed harvests and high fossil fuel costs, and precipitated social unrest around the world – while the food price index jumped almost 40 per cent from 2020 to September 2022.

A complex web of factors now grips global food markets.

Shutdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic and economic recessions have left cash-strapped governments in the global South with little ability to respond to new crises. Climate disasters have damaged food production in almost every region of the world, while farmers face soaring energy costs and fertiliser shortages. And conflicts in Europe, Africa and the Middle East have affected global food supply chains.

Communities in 19 regions that are already experiencing acute food insecurity – known as ‘hunger hotspots’ – are likely to face even tougher conditions going into 2023, the FAO and the World Food Programme warn. People are facing starvation in Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Nigeria, South Sudan, Somalia, and Yemen, with 222 million people in 53 countries and territories expected to need urgent assistance.

Most of the world’s food needs are met by four staple crops – wheat, rice, maize, and soybeans. These crops are highly fertiliser dependent and account for the majority of global intake of calories. Nitrogen, phosphorous and potassium are the primary nutrients in fertilisers: all are derived from fossil fuels and require large amounts of energy to process.

While international prices for wheat and other staple foods have come down after the spike that followed Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – two of the world’s biggest wheat producers – the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) warns that it would be premature to conclude the global food price crisis is near an end. “Domestic food prices for consumers continue to rise in most countries,” the IFPRI said in a September analysis.

After a brief pause in the price rise for fertilisers over the northern hemisphere’s summer, fertiliser prices are rising again. High fossil fuel energy costs in Europe have curtailed fertiliser production there, with the World Bank forecasting the continent will become a net importer of fertiliser and put further pressure on global markets. All major fertiliser exporters – led by Russia, China, Canada and Morocco – have limited stocks available, the World Bank says. Brazil and India are two of the largest importers of fertilisers.

The food price crisis highlights how interconnected energy and food security are, according to an analysis from the International Energy Agency. “Higher energy and fertiliser prices therefore inevitably translate into higher production costs, and ultimately into higher food prices,” IEA analysts Peter Levi and Gergely Molnar said.

The cost of living

The SciDev.Net investigation revealed that in August the cost of an egg jumped from US$0.12 to US$0.23 year-on-year in Buenos Aires, Argentina. In the Philippines’ capital Manila, one kilogram of onions cost around US$0.75 a year ago; in August it cost US$3.38. Some of the most severe rises were in the cost of chicken, which is now beyond reach for millions worldwide.

SciDev.Net spoke with grocery shoppers to find out how they are coping with rising food prices. Families are responding by limiting their diets and reducing the quantity of food purchased, while many are calling for government intervention and price regulations to limit price gouging.

“It is true that wholesale and retail products are becoming more and more expensive. But the shopkeepers abuse it,” Bineta Diallo, a shopper in the Ouakam district of Senegal’s capital Dakar tells SciDev.Net. “Everyone sets their own price. It would be good for the government to regulate prices and set up a verification mechanism.”

Governments worldwide have responded to the latest food price spike by cutting fuel taxes, increasing subsidies and imposing price controls on food and energy products. The World Bank argues, however, that such measures are usually costly and do not tend to benefit low-income households.

In 2020, global food insecurity rose as much as it had in the previous five years combined. The number of undernourished people increased by around 160 million to 811 million, with the most significant rise in Africa, where one fifth of the population was undernourished. Between 702 and 828 million people were affected by hunger in 2021, the annual multi-agency food security and nutrition report revealed.

The latest available evidence suggests that the number of people unable to afford a healthy diet around the world rose by 112 million to almost 3.1 billion, reflecting the impacts of higher consumer food prices during the pandemic, the report says. “This number could even be greater once data are available to account for income losses in 2020,” it predicts.

Beasley, the WFP chief, told the UN Security Council last month that up to 345 million people in 82 countries were “moving towards starvation”. He added: “This is a record high – now more than 2.5 times the number of acutely food insecure people before the pandemic began.”

Juana Ortiz, a shopper interviewed by SciDev.Net at a Walmart supermarket in Mexico City, says: “Now that everything has gone up in price, I have to think better about what I am going to buy or what I am going to make to eat, especially for dishes that need several ingredients, such as adobo or mole. There are products that sometimes I don't buy, such as potatoes, which are very expensive.”

“At least three times a week, my children and I have to eat at the common pot because I do not have a stable job and my husband lost his job due to COVID-19,” says Rosa Márquez, a street vendor who sells trinkets from the doorway of a high-end wet market in Lima, Peru’s capital. ‘Olla común’ – the common pot – is a way for people in poverty to share resources: women in slum areas cook food donated by traders or shoppers. Each pot can feed more than 100 people for free, or for a nominal cost of around US$0.25.

“Other times, buyers give me some things, like vegetables or fruits, with goodwill,” says Márquez. “Even so, some days my husband and I eat just once because we prefer our children don’t go to bed with their stomachs empty. I can't buy enough food for them at these prices.”

There are now several thousand common pots registered with government food councils in Peru, with the majority in Lima. High unemployment along with food price inflation are devastating the ten million people in Peru who live on US$3 or less per day, while in nearby Venezuela and Argentina, nominal food inflation is at 131 per cent and 71 per cent respectively.

Communities across Asia are also struggling with maintaining a sufficient diet. According to Fermin Adriano, a former Philippines undersecretary of agriculture, soaring food prices are causing widespread malnutrition and stunting among children. The Philippine government has proposed a nearly 40 per cent increase in funding for the agricultural sector in its 2023 budget, including doubling its allocation to the National Rice Program to expand fertiliser support for farmers.

While rice growing conditions remain favourable in South-East Asia for upcoming wet and dry season rice harvests, the early warning crop monitor from the intergovernmental Group on Earth Observations’ Global Agricultural Monitoring Initiative says that fuel and fertiliser shortages are likely to result in below-average yields in Sri Lanka and are causing concern in Nepal.

India announced in early September that it was restricting exports of broken rice – fragments of rice which have been broken in the field or during processing but are still edible. Within days the price of broken rice had risen by around US$20 per metric tonne in East Asia and the Pacific, according to the World Bank’s September food security update.

India is the world’s largest rice exporter, but it has been hit by inflation and poor grain production. Meanwhile, a plant disease first identified in China has been detected in paddy fields in northern India, raising fears that the southern rice black-streaked dwarf virus could reduce yields by 30 to 50 per cent.

Food export bans

Restricting or banning food exports to protect local communities can have mixed results, Rob Vos from the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) tells SciDev.Net. Currently, about 17 per cent of traded food products are under some level of export restriction, he says.

“That’s big in commodity markets,” says Vos, IFPRI’s markets, trade and institutions director. “And actually the 17 per cent is more than what we saw at the height of export restrictions in the 2010-2011 crisis.”

Vos says that global prices for rice, wheat, maize and vegetable oil have been affected by export bans, while volatile market prices give rise to further speculation by traders and investors. “Importers in countries don’t know how to adjust prices or what to expect next. That typically is a bad signal,” Vos adds.

“Famine doesn’t occur overnight. It can be prevented. We have enough food around the globe to feed the world.”

Csaba Kőrösi, President of the UN General Assembly

Michael Fakhri, the UN special rapporteur on the right to food, agrees that governments should avoid introducing unilateral export bans that could further destabilise markets – with the exception of low-income states, which Fakhri says will need the option to ban exports more quickly.

A study published in Nature Food in September modelled the potential implications of reduced wheat and maize exports from Ukraine and Russia. The researchers predicted that maize prices would increase up to 4.6 per cent in the coming year, and wheat costs would rise 7.2 per cent. While they say that increased wheat and maize production in other regions could provide partial compensation for expected export declines and dampen rising prices, this would come at the cost of a rise in carbon emissions.

The world is tipped to reach a population of eight billion next month. Since the 2008 crisis, the fight against hunger has been high on the international agenda. But the slow pace of action barely reflects the potential scale of disaster, and the number of hungry and undernourished people in the world continues to grow.

At this month’s 50th session of the Committee on World Food Security, the president of the UN General Assembly, Csaba Kőrösi, told ministerial delegates that food insecurity was linked to global inequalities. He argued that the fight against hunger should rely on data and scientific evidence.

“Famine doesn’t occur overnight. It can be prevented,” Kőrösi said. “We have enough food around the globe to feed the world.”

“Every day, product prices are rising,” Adja Sokhna, a shopper at the Castor market in Dakar tells SciDev.Net. “We were told that it is because of the war between Ukraine and Russia. But what I don't understand is the rise in the price of certain products such as vegetables that are produced in Senegal.”

Many low-income countries like Senegal operate what Vos calls a dual market – a modern supply chain operated by international agribusinesses that produce food for export, and a local food system run by traditional smallholders.

Local producers lack access to infrastructure such as cold chains, resulting in high food loss. “That could be part of the problem, the supply chain for the domestic market is much less developed than the supply chain for international markets,” Vos says.

All of this leaves families like Sokhna’s facing an uncertain future. “We have the feeling of being abandoned by the state, which does nothing to regulate prices,” she says.

Future-proofing food systems

Fakhri argues that pandemic-era policies that supported food access should become permanent programmes, such as direct cash transfers, universal school meals, and support for smallholders, pastoralists, fishers and other small food producers. In a report due to be delivered to the UN General Assembly in late October, Fakhri says that country-level food hoarding should be discouraged. He says there should be transparency in national and corporate food stocks and calls on countries with large food stocks to support those in need.

Governments and agricultural research teams are considering the viability of non-fossil fuel-based fertilisers. Meanwhile, climate resilient crops and livestock breeds are the focus of research around the world. But in the short term, farmers and supply chains are largely unable to alter production patterns, says Vos.

The food that we buy and eat today was produced six months ago using fertilisers that were sourced 12 months ago. Vos points out that winter wheat crops will be sown in the northern hemisphere over the coming weeks, and alternative fertilisers will not be available. In general, farmers lack the flexibility to pivot towards new food products, says Vos – coffee trees take several years to fruit, for example, and each food needs specific equipment, inputs, climate and expertise.

Sebastian Nduva, from the non-profit International Fertilizer Development Center, says that field trials in Rwanda have revealed that the 1.5 to 2 million tonnes of fertiliser that will be missing from Sub-Saharan Africa’s 2022/2023 cropping season will result in losses of more than 30 million tonnes of grain – enough, Nduva says, to feed 60 million people.

“This is a conservative figure if we factor in the climatic risk of inadequate rainfall currently ravaging most parts of East and Southern Africa,” says Nduva, who heads up the IFDC’s AfricaFertilizer.org programme, which collects and processes statistics for key fertiliser markets in Sub-Saharan Africa. “We have seen farmers in Sub-Saharan Africa opting to do their cropping without fertilisation or with reduced fertiliser quantities. The price of fertiliser year-on-year has gone up more than 100 per cent in most jurisdictions and we don't expect those levels to normalise anytime soon.”

Tensions now lie between the urgent need for immediate solutions to the growing hunger crisis, and the longer-term systemic changes critical to avert future famines.

This is a tension that the Committee on World Food Security is all too aware of. André Luzzi, a member of the committee’s civil society and indigenous peoples’ consultation group, told the ministerial segment: “We need urgent short-term measures, but they must not make the crisis worse in the long term. Simply scrambling to find new sources of fertiliser is not compatible with the demand from many producers … to end the chemical treadmill of production in the long term.”

Alvaro Lario, president of the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), said the structure of food systems and “glaring inequalities” were needed to address the current food crisis. “We must address immediate needs, but not at the cost of investing in longer term solutions. We cannot continue to move from crisis to crisis,” Lario said at the opening of the committee’s 50thsession.

Small-scale producers are key to reversing alarming global trends, Lario said. Despite significant challenges, smallholders produce around one third of global food calories on less than 11 per cent of the farmland. He called for financing for climate change adaptation for small-scale farmers, infrastructure investment to help smallholders get their produce to markets, and prices that fairly compensate farmers.

And while women and girls bear the biggest brunt of the food crisis, they may also be central to future solutions, Luz Haro Guanga, executive secretary of the Network of Rural Women of Latin America and the Caribbean, points out.

“Rural women are the guardians of life, water, natural resources, seeds and healthy food,” Haro Guanga told the committee. “Although women and girls constitute 90 per cent of the producers and providers of food to their households, they are usually the ones that eat last and the least. We want to have the support of international organisations that believe, like us, that without women there is no democracy, no future, and no sustainable development.

“Every penny invested in rural women is sowing fertile land.”