Written by Oumou Camara, Regional Director, North and West Africa; William Adzawla, Economist; and Prem Bindraban, Project Director, Fertilizer Research and Responsible Implementation (FERARI) / Posted Courtesy of Fertilizer Focus

Agriculture is a vital sector of Africa’s economy. In 2021, the sector employed 65% of the labour force and achieved 59% of the African Union (AU) Agenda 2063 goal of modernizing agriculture for improved productivity and production. Yet, the continent is off-track in achieving the zero-hunger target, as the 2019 prevalence of undernourishment (19.1%) is projected to rise to 25.7% by 2030 due to a failure to harness the full potential of the agriculture sector. For decades, agriculture has been one of the topmost priorities in developing Africa, especially with its multiplier effect on the economy. Agricultural transformation is therefore necessary for Africa’s development.

Considerable steps have been taken in African agricultural development and transformation. Noteworthy are the creation of the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD), the Maputo Declaration of 2003, and the Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP).

Countries and regional economic communities (RECs) have developed national and regional agricultural development plans and investment plans to guide transformation of the sector. Renewed commitments include the AU Agenda 2063, the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA), Abuja Declaration on Fertilizer for a Green Revolution in Africa, African Development Bank’s (AFDB) Technologies for African Agricultural Transformation initiative, the UN Food Systems Summit and the World Bank’s Food Security Research Project.

However, these have not resulted in transformation. Only a few countries are allocating 10% of their total public spending to agriculture. Growth in crop production has largely been due to expansion in cultivated area, and the resulting loss of biodiversity and degradation of soil quality is unsustainable.

This article reflects on agricultural transformation developments and strategies in Africa. The biggest agricultural development trends, shocks, and challenges in Africa will be discussed. Noteworthy strategies the AU, RECs, AU member states, and the development community have instituted thus far will be considered. Then reflections will be made on the policy and strategy gaps that need to addressed to ensure Africa’s vision of no child going to bed hungry.

Challenges and opportunities

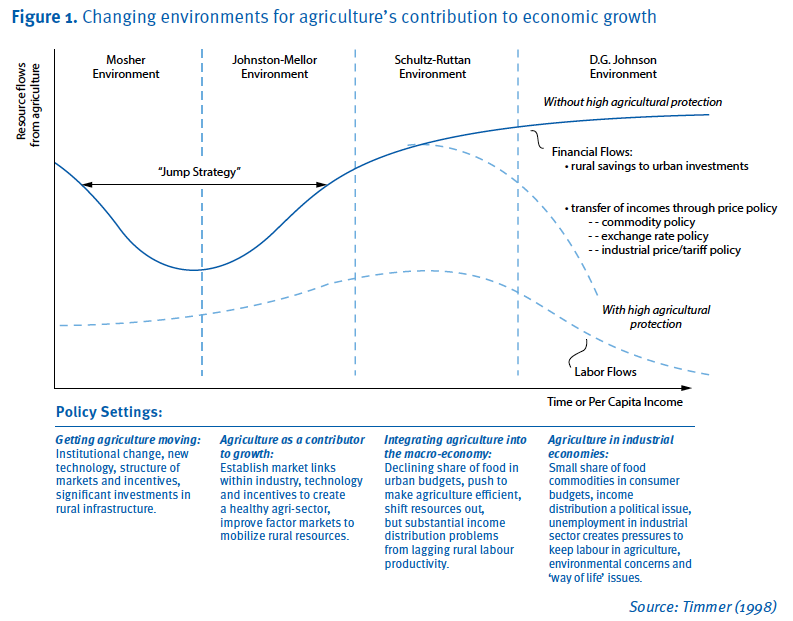

Generally, economic transformation requires that agriculture contribute not more than 10% to GDP alongside increased urbanization. Agricultural transformation requires a shift from subsistence farming, characterized by resource under-utilization, to commercial agriculture, characterized by efficient resource utilization (see figure 1). This can be attained through improvement in labour productivity and infrastructure – unfortunately, these are insufficient in almost all African countries. Land degradation and poor land tenure, climate change and low adaptation with resulting water deficits, low technology and education among farmers, inadequate financing hindering investment in agricultural research, underdeveloped infrastructure including irrigation, markets and roads, low information and its asymmetry, and a weak agricultural value chain are key challenges to the transformation of African agriculture. Although agriculture is largely a private-sector activity, public policies must provide a suitable production environment for farmers.

Despite the challenges, the opportunities for transforming Africa’s agriculture exist. Firstly, Africa has vast arable land, providing an opportunity for transformation through largescale production. Effective land tenure arrangements and adoption of appropriate technologies would facilitate this.

Secondly, the rapidly increasing population, with an annual average growth rate of 2.45% relative to 1% globally, suggests high food demand in Africa. As a result, more food must be produced to meet the needs of the people. Although the associated increase in youth unemployment is concerning, it provides an energetic pool of human resources for agriculture, especially as most are well educated. The disposable income of Africans is also increasing, boosting the demand for diversity and quantity of food. If domestic production is not sufficient to meet the needs of the people, then considerable food must be imported, which will further increase the trade deficit and depreciate the national currencies. The rising urbanization of African economies engenders huge agricultural markets and opportunity to transform the livelihoods of farmers.

And thirdly, the rising commitment and enabling public policies, such as fertilizer subsidies, create opportunities for increasing agricultural productivity in Africa. Even under favourable socio-economic and policy conditions that allow agricultural growth, a proper agro-technical strategy should be pursued. Given that organic and green manure is limited, production systems can only be lifted to a higher level with external additions of nutrients through mineral fertilizers. Equally important is water availability to ensure its interaction with fertilizer can boost the efficiency of each.

Strategies and developments

With the establishment of the NEPAD Secretariat in 2002, African countries acknowledged that economic growth was not possible without agricultural development. This led to adoption of CAADP and related policy frameworks to guide transformation. In these documents, countries have examined their unique constraints and opportunities and elaborated national agricultural development strategies and investment plans. Under CAADP, African country leaders commit to allocating 10% of their budget to the agriculture sector, 1% of which goes to agriculture research, to ensure 6% agricultural growth. In 2018, the NEPAD Planning and Coordination Agency became the African Union Development Agency. As such, the institution aims to provide “knowledge-based advisory support to AU Member States in the pursuit of their national development priorities.” This reflects AU’s Agenda 2063 of modernizing Africa’s agriculture and agribusinesses, especially through expansion of modern production systems and technologies to eliminate the traditional hoe and cutlass systems, providing a conducive environment for the involvement of women and youth in agriculture.

The enormous plight of smallholder farmers in Africa, compared with the ‘Green Revolution’ success in Asia and Latin America, has triggered concerns, resulting in the Abuja Declaration in 2006 for increased fertilizer usage alongside improved seeds and other good agronomic practices. The launch of AGRA in 2006 aimed to transform African agriculture from subsistence to a commercial system to reduce poverty, improve food security, and ensure equitable growth through innovation and improved access to markets and finance. AfDB’s Feed Africa component of its High 5 initiative incorporated the Strategy for Agricultural Transformation in Africa 2016-2025, seeking to end hunger and poverty and improve the export potential of the region. Africa also took part in the 2021 United Nations Food Systems Summit that proffered solutions to the global unsustainable, unhealthy, and unfair food system.

African soils are losing nutrients due to inadequate replenishment

Transforming Africa’s soil health

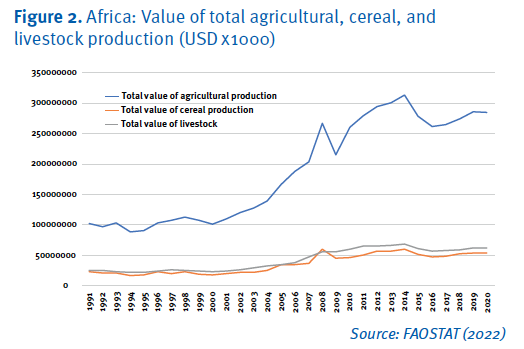

Despite these programmes, African agriculture has not seen much progress or transformation. For instance, although the total value of agricultural production has increased since 2000, cereal and livestock production, crucial to the population’s food security, remains almost stable (see figure 2). The high diversity in the agroecology, development of infrastructure (particularly irrigation schemes), and low adaptation potential to the changing climate have resulted in diverse country-level achievements. The success of Ethiopia in its agricultural transformation agenda, with an over 6% growth in the sector over 25 years and a corresponding drop in poverty, demonstrates the possibility of achieving the CAADP objectives.

Henao and Banaante demonstrated that, since the first Africa Fertilizer Summit, 85% of African farmlands have annual nutrient mining rates of more than 30kg/ha. African soils are losing billions of nutrients without adequate replenishment. The continent’s soil capital base is rapidly eroding, affecting its capacity to achieve the productivity increases needed to feed the growing population. Fertilizer application rates have increased to 16kg/ha since the summit, and fortunately, that increase is driven by higher application rates (intensification), not expansion in land area (extensification). But fertilizer use remains far below the Abuja Declaration target of 50kg/ha.

Inefficiencies in the fertilizer supply chain must be addressed

Only four countries in sub-Saharan Africa have reached that application rate. And most of the fertilizers used consist of outdated blanket recommendations, mainly focused on primary nutrients. So farmers are not only using insufficient fertilizers, but the limited volume they use does not contain the required nutrients.

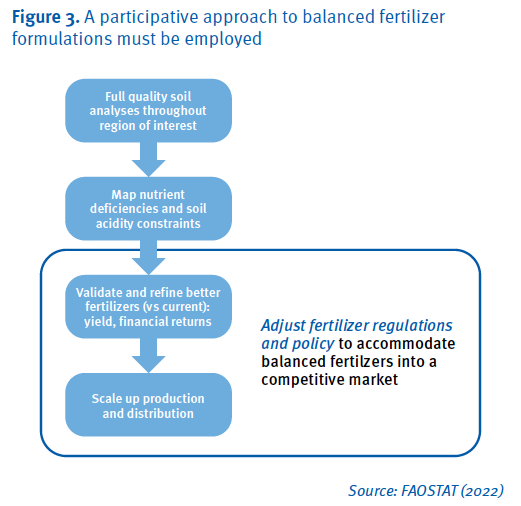

This interplay between various natural production factors forms the basis for raising the economic and labour productivity of the system. An additional dimension to this strategy is the need to fine-tune agronomic practices to be situation specific. This is where spatial approaches, such as soil and crop mapping and quantitative watershed analyses, supported by data, provide an overview of what actions to take. This will guide logistical processes in fertilizer and other input chains and assist policymakers through assessment of spatially explicit production estimates. In turn, input and output chains can become more efficient, driving prices down.

Once a framework has been established to prioritize sustainable investments in soil heath by national governments and the private sector, and once research has identified the best innovations to address nutrient depletion and emerging climate change-related issues, such as drought, dry spells, and flooding, to sustainably improve soil health, then comes the farmer-led implementation perspective: How do we ensure that these technological innovations are accessible and affordable at the right time and the right place for farmers? And how do we ensure sustainable adoption of these technologies by small-scale farmers?

Crop response

A smarter approach is needed to sustainably increase the use of appropriate fertilizers in Africa. The production frontiers can be pushed outward by addressing secondary and micronutrient deficiencies, with yield increments ranging between 1.1-1.6t/ ha. To effectively increase the use of appropriate nutrients by smallholder farmers, not only must farmers be given an incentive (through remunerative output markets) and capacity (access to knowledge and finance) to use fertilizer, supply-side inefficiencies leading to high transaction costs, low quality, and high farm-gate prices must be addressed.

Scientists and policymakers must work with farmers to ensure that fertilizers are not only crop- and site-specific and address primary, secondary, and micronutrient deficiencies that limit soil health and crop response, but also take into consideration socio-economic conditions and cost-effective locally available resources.

Inefficiencies in the fertilizer supply chain must be addressed to minimize transaction costs and reduce the farm-gate price of fertilizers. This can be done through investments in smart financing, as well as port, warehousing, and distribution infrastructure. The public sector must play its role in the provision of public goods and advisory services to ensure that the fertilizer that reaches farmers is of good quality and used professionally. The fertilizer market is capital- and logistics-intensive; therefore, quality can deteriorate between the time of its import and its availability in agro-dealer shops. Having the right legislative, regulatory mechanisms, and public advisory service provision in place, coupled with effective quality control enforcement, is crucial to sustainably transforming Africa’s soil heath.