Table of Contents

Summary | PAPAB at a Glance | Outcomes of PAPAB | Publications | Conclusions | Annexes | Contact

Download PDF

English | French

Summary

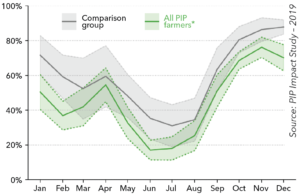

Sustainably Increasing Agricultural Productivity in Burundi

The Supporting Agricultural Productivity in Burundi (Projet d’Appui à la Productivité Agricole au Burundi – PAPAB) project has sustainably increased agricultural productivity, strengthened resilience and raised incomes for 865,666 farming households (Component 1 – Year 2019) and 59,575 farming households (Component 2). A 2019 impact study carried out to assess the Integrated Farm Planning (Plan Intégré du Paysan – PIP) approach showed that over 80% of PIP households have significantly increased their incomes over the past three years. According to this study, the percentage of PIP households stating that they did not have sufficient food throughout the year is significantly lower than non-PIP households, which reflects a greater level of resilience among PIP households.

Line represents percentage of farmers reporting to have inadequate, or barely adequate, food each month. Shaded areas are 95% confidence intervals, n-897.

*Computed using sampling weights to correct for overrepresentation of earlier generations in the sample.

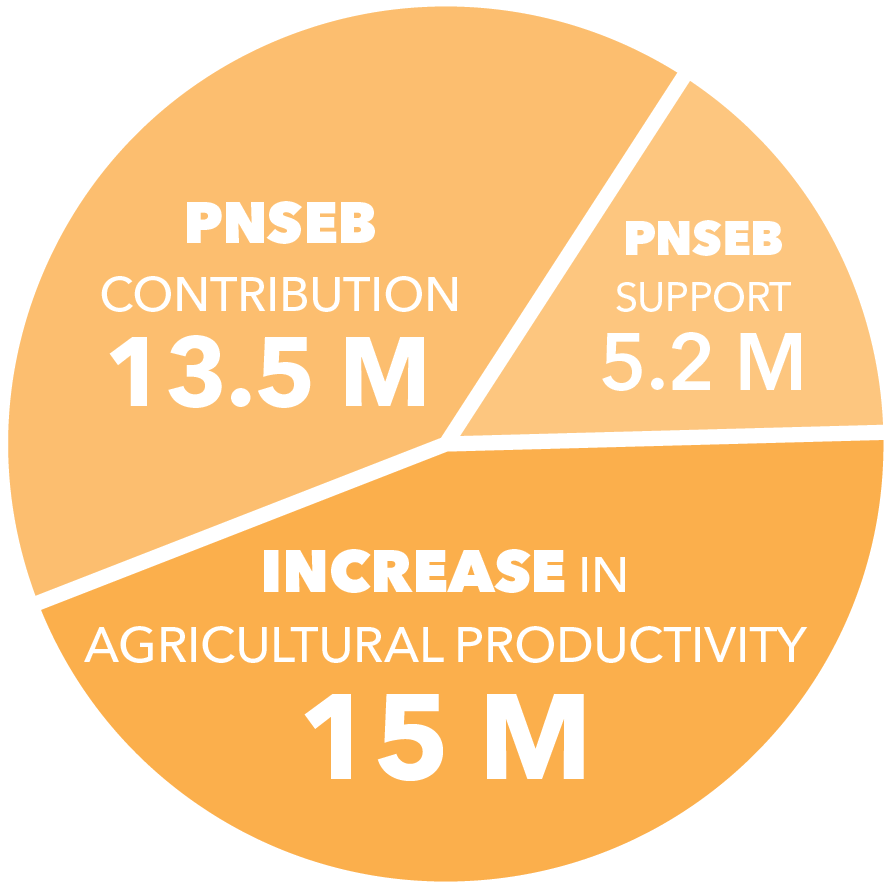

The PAPAB project operated for four-and-a-half years, from November 2015 to May 2020, through a grant from the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. The project was implemented by a consortium of seven partner organizations (IFDC [project lead], Alterra/Wageningen Environmental Research [WENR], Oxfam, ZOA, Réseau Burundi 2000+, OAP and ADISCO). PAPAB also partnered with a public entity, Technical Services of the Ministry of Environment, Agriculture, and Livestock (MINEAGRIE), as well as private entities, including Tanga Oil, to promote the cultivation of patchouli. The project focused its activities on: providing technical support to strengthen the National Fertilizer Subsidy Program in Burundi (Programme National de Subvention des Engrais au Burundi – PNSEB); contributing to the Common Fund for Soil Improvers and Fertilizers to help support the distribution of subsidized fertilizer through PNSEB; and providing direct support to farmers to sustainably improve the management of their farms in an integrated, more resilient and responsible way.

PIP: Integrated Farm Plan

A PIP is a three- to five-year plan developed by all members of a household that aims to significantly improve farm management in an integrated and sustainable manner. The PIP is the basis for the emergence of a self-help dynamic among the household members.

PAPAB and the Agricultural Productivity Issue

In January 2015, a workshop on the Theory of Change took place around the “soil fertility” issue. This workshop stressed that Burundi was undergoing a severe soil fertility crisis. It also underlined the importance of developing synergy among the different projects working toward increasing agricultural production and conserving soil and water resources. Hence, the need arose for setting up a new project to continue supporting PNSEB and reinforce the desired impact, within a sustained and integrated framework, in order to meet various preconditions and trigger a sustainable increase in agricultural productivity. This laid the foundation for the PAPAB project, which initially was planned for four years, from November 2015 to December 2019.

The root cause of the stagnation of agricultural production in Burundi is the low productivity of agricultural land resulting from a combination of factors including: low access to and poor use of fertilizers (organic and chemical) and soil amendments, limited access to improved seeds, farming practices unsuitable for restoring and preserving soil fertility, low agricultural income, and farmers’ inability to invest in their farm business. Restoring and optimizing the potential of the use of fertilizers and soil nutrients by diversifying fertilization practices, and supplying crops with nutrients from sources other than chemical fertilizers, are the main issues that PAPAB aimed to tackle through its two components: (i) improving soil fertility through consolidating fertilizer and soil amendment supply systems and (ii) increasing farming productivity and resilience, organizing farmers and facilitating access to markets.

KEY OUTCOMES OF THE PAPAB PROJECT

Increased Rates of Fertilizer Use

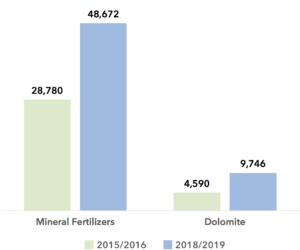

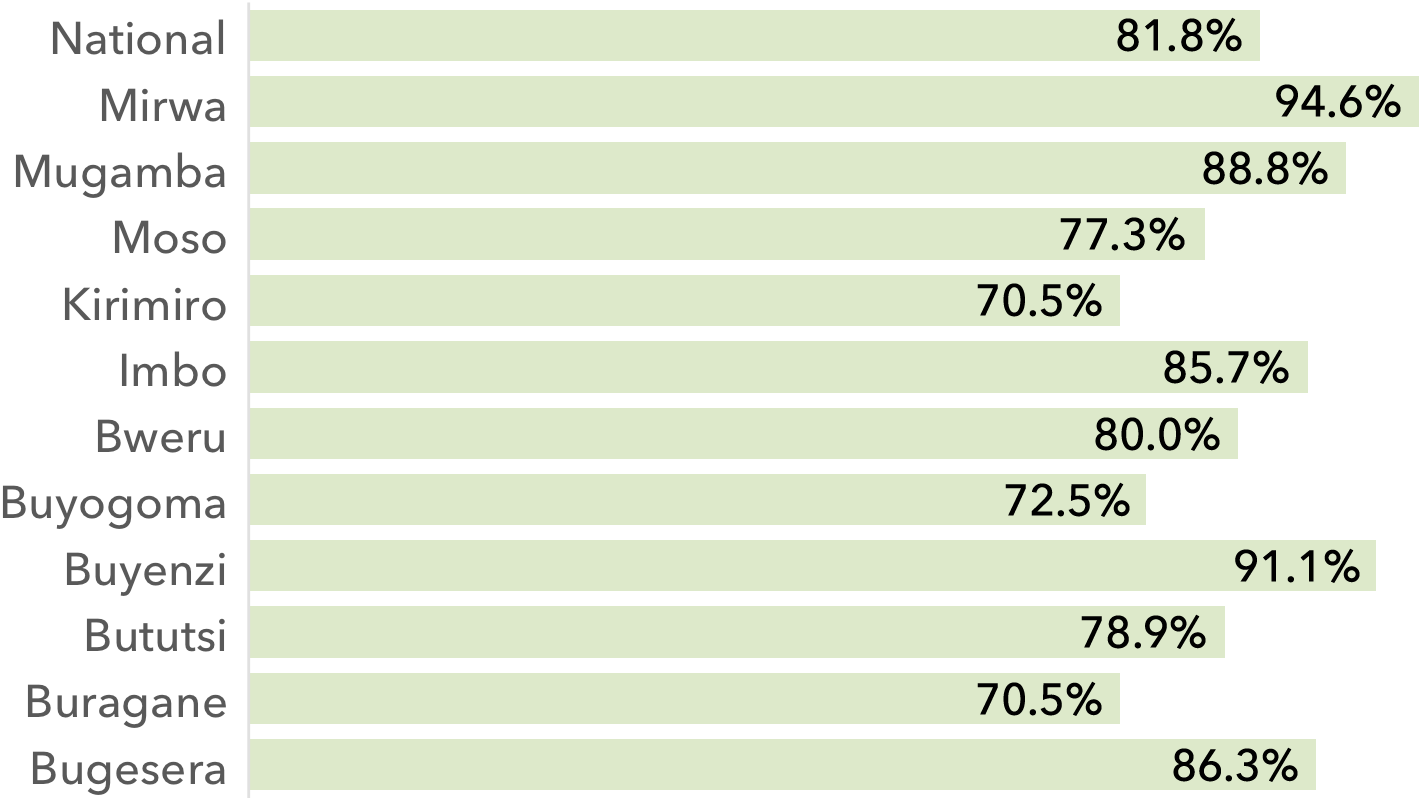

The number of farmers enrolled in PNSEB increased significantly with the implementation of the PAPAB project, from 625,892 in 2016 to 865,666 in 2019, a growth rate of 38%. In 2019, an estimated 48% of Burundian farming households had access to fertilizers through PNSEB. Fertilizer use increased 69% during this period and dolomite use increased 112%. This led to substantial increases in agricultural production. The PNSEB impact assessment study showed that 81.8% of farmers were more satisfied with their level of their agricultural production compared to the period before PNSEB.

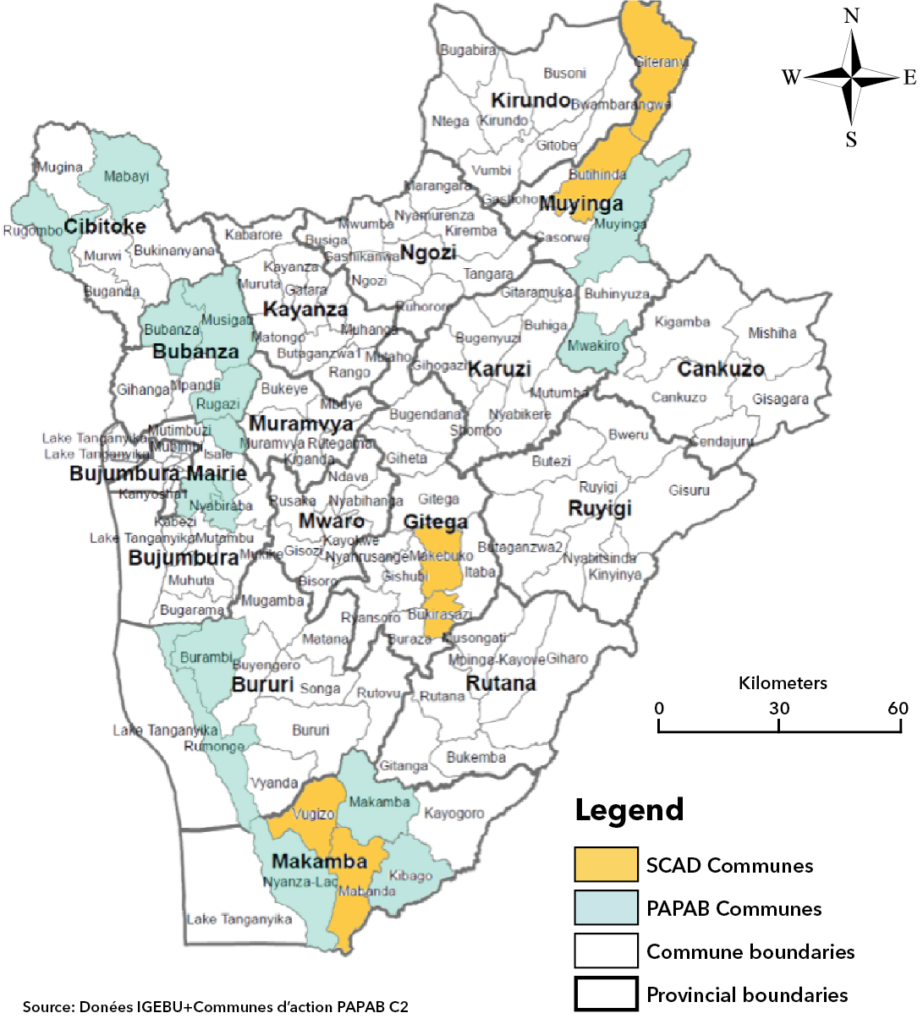

Extension of the PIP and ISFM Approaches

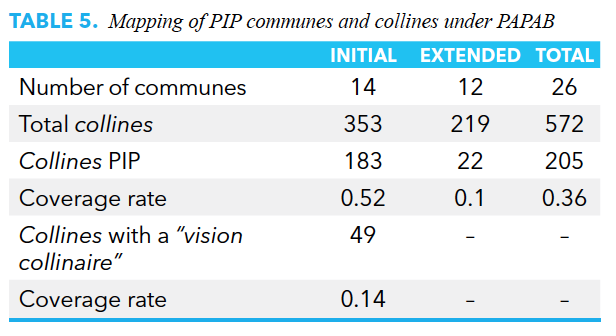

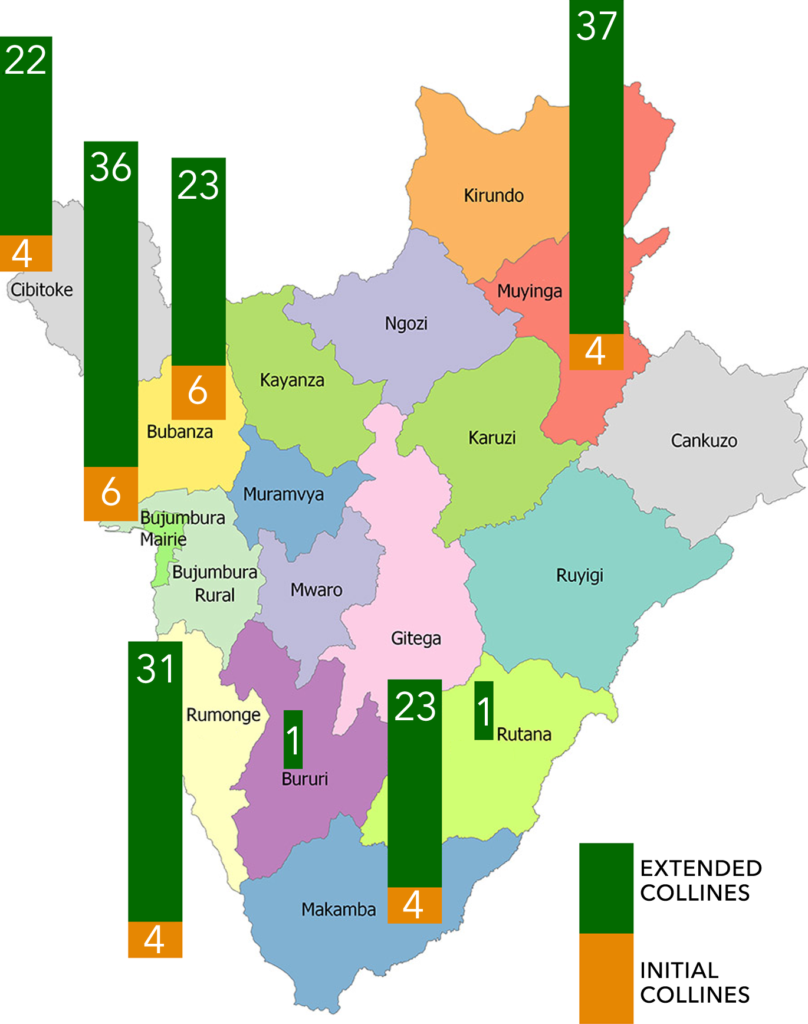

The PIP approach promoted by the PAPAB project has been adopted by 59,575 households, extending the project coverage now to over 205 collines (or 26 communes) across the six initial target provinces; 49 of these collines have developed their own visions collinaires.[1] This number should continue to grow since emphasis has been placed on farmer-to-farmer training through the continuous extension of the PIP and integrated soil fertility management (ISFM) approaches, which will be strengthened by other ongoing projects (mainly PAPAB+[2] and PAGRIS [3]). PIPs form the basis of a continuing process of self-promotion and sustainable development, whereby farming households and communities get involved and organized to implement their individual and community projects.

Financial Inclusion and Access to Finance

Under the PAPAB project, individual and joint initiatives have been strengthened and supported by on-demand technical trainings and facilitation activities to promote the organization of participating households through 1,305 Solidarity Groups for Savings and Loans (GSECs). These informal structures have also largely contributed to strengthening resilience and social cohesion within target households and communities, while triggering organizational dynamics around savings and loans principles, which has gradually led to financial inclusion. These initiatives have also set the stage for more formal structuring dynamics around entrepreneurial and community activities. This has provided project beneficiaries with the opportunity to connect with financial institutions and other market players, while developing specific capacities and services to meet common needs.

Structuring of Producers and Market Access

Increased agricultural production has been a motivating factor in organizing farming households into farmer-based organizations (FBOs) and cooperatives, mainly to develop services aimed at improving post-harvest management (including storage) and access to markets. A total of 179 Integrated Collective Plan (Plan Intégré Collectif – PICs) structures, 93 FBOs and 40 cooperatives have been established. With support from the World Food Programme (WFP), actions have been taken to provide these community-based structures with quality storage equipment, such as plastic silos and conservation bags. Through the Communal Approach to Agricultural Markets (Approche Communale de Marché Agricole – ACMA), the PAPAB project has also promoted the networking of actors and stakeholders, including FBOs and cooperatives, with microfinance institutions (MFIs) and local traders, with a view to facilitating sales of agricultural products at better prices. A total of 25 cooperatives are now operational and the relevant bodies have been authorized to conduct their management activities in accordance with their business plan. However, the structuring process, and the post-harvest management system in particular, will need a monitoring and supporting framework after the closure of the PAPAB project to advance their activities and sustain their self-empowerment.

PAPAB at a Glance

Partners | Intervention Zones | Outcomes

Project Stakeholders

NGO Partners

Private Sector Partners

Main Outcomes of Component 1

2015/2016

625,892 Farmers

28,780 mt of Fertilizer

2018/2019

865,866 Farmers

48,672 mt of Fertilizer

Main Outcomes of Component 2

59,575

Total Households with a PIP

205

Total PIP Collines

1,305

Total Savings & Loan Groups

272

Total Farmer Organizations

40

Total Number of Cooperatives

INTEGRATED FARM PLAN (PIP)

The Integrated Farm Plan, or “Plan Intégré du Paysan” (PIP), is a methodological approach to bring about a change in mentality, whereby farming households and communities learn to develop and invest in a vision supported by an integrated plan of change toward a desired future. The PIP approach is based on beneficiaries’ awareness of their current situation and their capacities and opportunities for change, taking into account the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats identified at the household, colline and community levels. In line with this, the PIP approach fosters self-management, knowledge sharing and responsible commitment for carrying out jointly defined activities (at household or colline level), including improved management of natural resources. Self-empowerment, integration and collaboration are the key principles of this approach.

SOIL FERTILITY TOOL (SFT)

A Soil Fertility Tool (SFT) refers to a set of techniques that use local soil data as well as online meteorological data to provide an overview of the level of accumulation/decomposition of organic matter and ultimately soil nutrient status. These data serve to formulate nutrient recommendations for different crops. In developing context-specific crop nutrient recommendations, several crop parameters come into play to reflect the local growing conditions at farm level. To determine these parameters, soil testing is conducted in a wet chemistry laboratory, and crop and biomass analyses are carried out, with several replicates, in different agroecological zones. With these parameters, the SFT can be calibrated to formulate recommendations. A validation process is required to assess whether the recommendations provided allow farmers to achieve the best results.

APPROCHE COMMUNALE DES MARCHÉS AGRICOLES (ACMA)

The Communal Approach to Agricultural Markets, or Approche Communale des Marchés Agricoles (ACMA), combines all actions aimed at providing direct economic players with training to enable them to remain competitive in a highly competitive market environment. It also facilitates the creation of partnerships between buyers (processors and traders) and farmer-based organizations (FBOs). The objectives of the ACMA approach are to : (i) strengthen the economic power of local operators in commercial transactions; (ii) increase supply and sales of agricultural products in local markets; and (iii) improve marketing conditions for agricultural products.

VILLAGE SAVINGS AND LOAN ASSOCIATION (VSLA)

A Village Savings and Loan Association (VSLA) is a village-level system managed by a solidarity group for savings and loans, whose members (15-30 people) decide to become organized to save money in the form of member shares. The savings generated go into a credit fund from which members can obtain loans repayable with interest. A VSLA is, therefore, a form of accumulating savings and providing loans, an autonomous and self-managed financial institution (managed by the community). A management committee of at least five people is entrusted with the collective management of the fund, but all members are responsible for the smooth running of operations. The main purpose of a VSLA is to ensure the accessibility of simple savings and loan programs within a community that does not have access to formal financial services. Under the PAPAB project, VSLAs have proven to be reliable sources of finance for PIP farmers.

IGG

Imigwi yo Gutererana no Gufatana mu nda (IGG), a Solidarity and Self-Promotion Group, is a type of association established and promoted by ADISCO. It is a social inclusion initiative in which a group of five to 10 farmers voluntarily get together for the purposes of mutual aid and solidarity in various self-development activities. IGGs have set the stage for the development of social and financial inclusion organizations, such as VSLAs, and serve as a basis for the structuring of cooperatives.

INTEGRATED SOIL FERTILITY MANAGEMENT (ISFM)

Integrated soil fertility management (ISFM) is an agricultural development strategy based on the combined and efficient use of a set of techniques to improve the availability and sustainability of water and various soil nutrients that crops need to increase land productivity. While not exhaustive, these techniques include the combined use of chemical fertilizers, organic manure, mineral amendments when needed, good quality seeds, soil protection and erosion control measures, improved farming practices, and other practices for preserving and improving soil fertility.

UNIVERSAL METHOD OF VALUE ACCESS (UMVA)

The Universal Method of Value Access (UMVA) is an electronic platform that offers tools and methods designed to facilitate the creation and management (technical and administrative) of an electronic database relating to financial transactions (opening and administering virtual accounts, orders, money transfers and online payments). The platform also supports community building among farming households. The UMVA system has been used by PAPAB mainly to facilitate grouped fertilizer orders and to support social and financial inclusion initiatives.

Outcomes of Component 1

Consolidating Fertilizer Distribution

Five outcomes are presented below with their main driving factors:

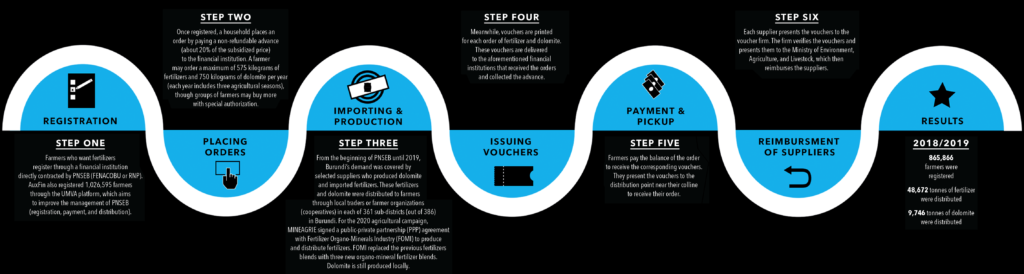

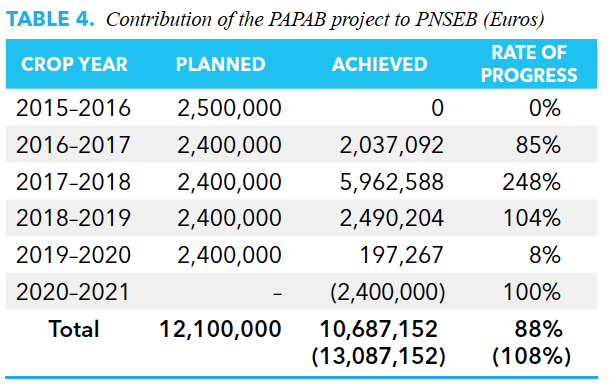

(i) Financial contribution to PNSEB, the National Fertilizer Subsidy Program (10,687,152 euros for the agricultural seasons between 2016 and 2020). With the gradual reduction of the subsidy rate from 60% to 30%, this contribution helped improve access to fertilizers for 48% of Burundian farmers (865,666 households in 2018/2019).

(ii) Technical and financial support to the Multimedia Unit of MINEAGRIE. This allowed for the timely and nationwide dissemination of key information relating to agricultural seasons, mainly seasonal fertilizer distribution programs, prices and terms of payment, and fertilizer application rates and methods. Within this framework, farmers were kept informed throughout the agricultural seasons, which helped prevent cheating and reduce fraudulent sales of fertilizers.

(iii) Facilitation of regular consultation frameworks for PNSEB stakeholders through Technical Committee for Fertilizers and Amendments (CTFA) meetings. This has made it possible to find timely solutions to problems arising unexpectedly during the agricultural seasons.

(iv) Organization of regular information meetings and trainings for PNSEB stakeholders and partners. The main topics discussed were related to innovations and new appropriate measures carried out. These meetings allowed for transparent management and the sharing of useful information among PNSEB partners.

(v) Specific studies conducted to support the implementation of the PNSEB program. The reports of these studies provide information on the strategic orientations and management of Component 1 (see trials on new fertilizer formulas, feasibility study for a local fertilizer plant, PNSEB evaluation study, audit of PNSEB accounts, etc.).

Increased Number of Households using Mineral Fertilizers

The use of mineral fertilizers promoted within the framework of IFDC’s Support Project for the National Fertilizer Subsidy Program in Burundi (PAN-PNSEB) project produced impressive results. However, under this project, the achievement of expected results was hampered by a number of factors including:

- Farmers’ poor awareness of the importance of using fertilizers.

- Difficulties with fertilizer payment due to the sparse network of counters for advance and balance payments.

- Inconsistent fertilizer orders due to poor communication on the agricultural calendar, fertilizer application techniques and ordering procedures.

With the PAPAB project, context-specific strategies were defined and set in motion to overcome the constraints listed above. These constraint-alleviating measures have significantly improved the recording of payment requests and fertilizer distribution operations as presented below:

- Highly committed involvement of the Provincial Office for the Environment, Agriculture and Livestock (BPEAE) in the collines has boosted farmers’ awareness and improved the recording of fertilizer demand. Thanks to PAPAB support to the Multimedia Unit of MINEAGRIE, tailored radio messages were broadcast, relayed and supported by BPEAE agents in their respective communes. This made it possible to convince many farmers who were still reluctant to use chemical fertilizers, which increased enrollment in PNSEB.

- Entry of new financial operators leading to the multiplication of payment counters for processing orders of fertilizers and limestone amendments. This was the case with National Federation of Cooperatives in Burundi (FENACOBU) and its 110 counters distributed throughout the country, which, together with Régie Nationale des Postes (RNP), brings the number of counters to a total of 233. This step facilitated and improved payment operations, which are remunerated by PNSEB at a rate of 3.7% of the amount collected.

- Introduction of grouped orders, thanks to the Social and Financial Inclusion Project[4] (launched on a pilot basis in three out of 17 provinces). This reduced the long queues at the counters, despite the strong increase in fertilizer demand.

- Computerization of counter services and capacity building of operators under PAPAB through technical assistance from PNSEB. This effort greatly improved payment and reporting operations.

- Exploration by PAPAB in 2018 of alternative ways to improve the efficiency of the PNSEB ordering and payment collection system. Following a call for applications to recruit an efficient operator to facilitate payments, BANCOBU and VIETEL (mobile telephone companies) were selected based on the assessment of their technical and financial proposals. These companies, respectively, proposed the use of mobile counters and an adaptation of the remote payment system (Lumicash). These options were implemented on a pilot basis and at limited scale, but the results were not conclusive. Despite their supposed user-friendliness, they could not attract as many households as expected, and BANCOBU eventually gave up. However, VIETEL persevered and has been authorized to operate in all provinces since 2020.

- Electronic registration introduced (in 2019) and adopted across the country to address the shortcomings and dissatisfaction that have long marked PNSEB registration procedures based on handwritten lists. This novelty was introduced and supported by AUXFIN in consultation with the local administration and BPEAE. The financial institutions involved in payment collection were facing serious problems (omission of names or incorrectly entered names) and, consequently, were led to register fictitious households that were not included in the PNSEB database. Through the AUXFIN UMVA platform, an electronic database was set up to register the total number of 1,026,595 farming households enrolled in the PNSEB, i.e., about 68% of farming households according to AUXFIN Geo-Structure. However, since this database was finally transmitted on May 6, 2020, IFDC has not been able to verify the data in the field.

This clearly shows that the number of households enrolled in the PNSEB project has drastically increased (38% based on data from the manual recording system and 64% based on data from the electronic database).

Increased Volumes of Fertilizers used by the Project Beneficiary Households

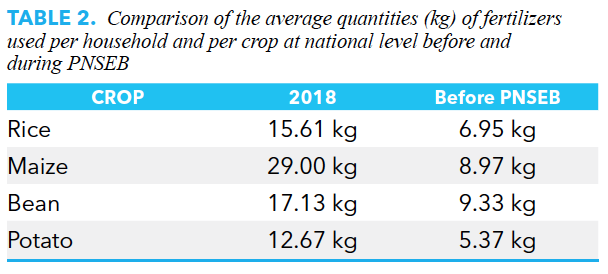

With the rising number of PNSEB farmers, the quantity of fertilizers distributed (all categories combined) increased by 69% and that of dolomite by 112%. This outcome was driven by the awareness-raising activities carried out by the project, supported by the conclusive and persuasive effects of fertilizer application in terms of increased yields on farmers’ plots, as part of the project strategy. This shows that, with an overall increase in crop yields, fertilizer use increased considerably, as farmers were more motivated to invest in their farms.

These data support the conclusions of the PNSEB impact assessment study, which noted a net increase in the average rates of chemical fertilizer used per household and per crop as an outcome of the project at the country level.

Farmers register and prepay their fertilizer orders at authorized offices. In exchange, they receive corresponding vouchers (September 2017).

Registration system by COOPEC agents within the framework of PNSEB (September 2017).

Registration system by COOPEC agents within the framework of PNSEB (September 2017).

Increased Agricultural Production

The PNSEB impact assessment study concluded that agricultural production also increased dramatically as a result of the increase in the number of fertilizer users and in the quantities of fertilizers imported and applied to crops. This study also reported that, while satisfaction levels vary depending on the cropping season and the region, 81.8% of respondents stated that their agricultural production had improved compared to the period before PNSEB. The highest satisfaction level was recorded in the Mumirwa region (corresponding to the Congo-Nile Crest, to the east of the Imbo plain).

The increase in the number of farmers enrolled and quantities of fertilizers applied is also partly related to the vast awareness-raising and communication campaigns that were systematically launched, with support from IFDC, before the period of balance and advance payments. Relevant press releases were read in churches and broadcast and posted by BPEAE services. Normally, fertilizer supply operations follow the logic of orders placed by zone with the advance payments. However, fertilizer deliveries were delayed on several occasions, often due to the lack of available foreign currency at importers’ level and some shortcomings at the input dealers’ level.

Proposal for a Professionally Managed Fertilizer Distribution System

Based on the weaknesses identified in the fertilizer distribution system, a training and awareness-raising program was conducted for PNSEB input dealers throughout the country in August 2016. This activity allowed collection of a substantial amount of information on this issue relating to a vital link of the fertilizer subsidy chain. It appeared that input dealers often lack the required skills and resources to effectively perform their functions since they are almost never chosen on the basis of their professionalism. Having assessed the situation, CTFA recommended that competent input dealers be selected following a call for applications and on the basis of specific criteria. The selection of zonal input dealers at the provincial level was carried out with financial and technical support from PAPAB in 2017 and 2018, and their work was expected to begin in 2019 season A. According to the guidelines established by CTFA, an assessment of distribution performance should be done for each fertilizer importer to gather sufficient information on the level of service delivery quality to better evaluate candidates during the selection process. However, this process was halted in 2019 due to the suspension of fertilizer imports in an effort to support local production with the new fertilizer plant, Fertilizer Organo-Minerals Industry (FOMI) coming onstream. FOMI is now equally in charge of fertilizer distribution at the zonal level.

Facilitation of Fertilizer-Related Operations by Setup of a Financial and Social Inclusion System (UMVA and G50)

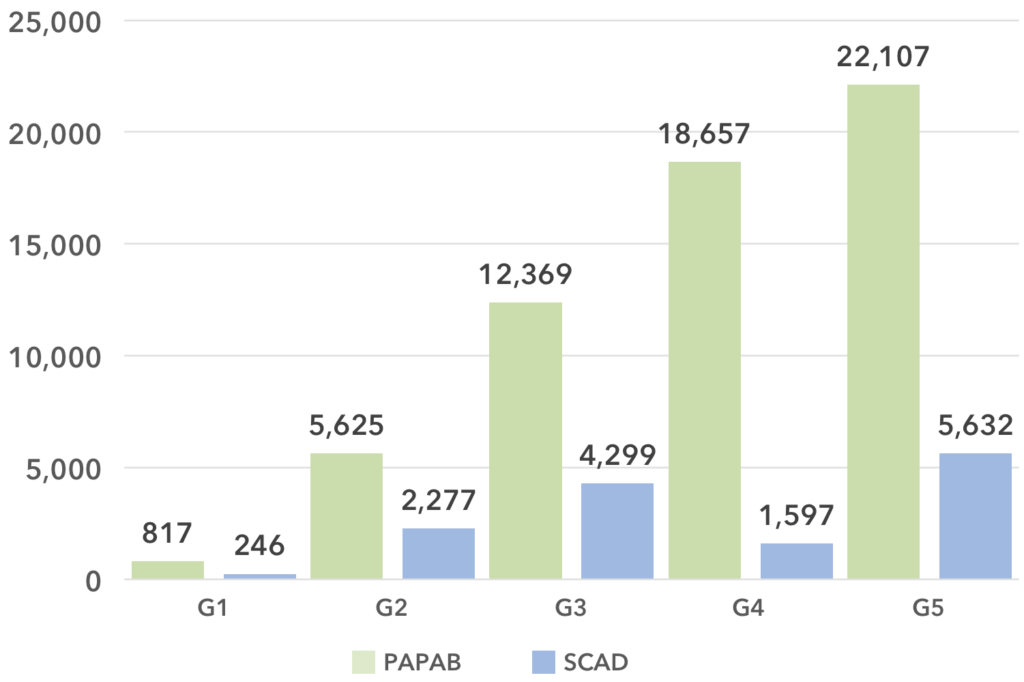

In support of PNSEB, IFDC collaborated with AUXFIN to set up a social and financial inclusion project aimed (through its technology and approaches) at consolidating credit-worthy fertilizer demand. In this context, AUXFIN has developed the G50 approach (an organized group of 50 local households) and introduced a new technology (the UMVA system) that facilitates farmers’ access to various services including financial transactions with MFIs (through individual and collective virtual accounts) and grouped fertilizer orders.

To date, 3,954 G50s, grouping 189,591 households, are monitored and supervised in the 17 project communes, including three communes in the Kayanza Province (Gatara, Kayanza and Muruta), three communes in the Karusi Province (Nyabikere, Bugenyuzi and Buhiga) and 11 communes in the Gitega Province (the entire province). These G50s have access to the ICT infrastructure (tablets and solar panels) to connect to the UMVA platform and perform various operations. The following activities have been carried out to achieve defined objectives and expected outcomes:

- Reorganized the G50 structure to improve the efficiency of operations and facilitate the registration of farmer groups as associations in their communes.

- Built group members’ capacity to use the UMVA system for their operations (39,100 people, including group leaders and five to 10 members per G50 know how to use the platform). All beneficiaries have easy access to basic financial services (trading account and electronic financial ecosystem via UMVA). The 189,591 enrolled farmers each have an individual trading account in the UMVA system; 30% of G50 members manage their operations (savings, transfers and payments) online via UMVA.

- Strengthened the savings service and extending its scope beyond the context of the PNSEB project by adding savings for seeds, insurance and various services: around 80% (136,008 households) of G50s made grouped payments via the UMVA system; 17,129 individual fertilizer orders were made via the system; 189,591 households have been informed about access to financing and the benefits of being connected to a MFI. They also have access to information related to health issues and agricultural insurance schemes.

- Prepared G50s to evolve into cooperatives and become autonomous: four pre-cooperatives were set up at the rate of one pre-cooperative per commune where the UMVA centers are located.

- Connected G50s to MFIs and other institutions: all members of the 3,954 G50s have individual accounts connected to the group account with the MFI.

- Facilitated remote access to information and services requiring a minimum of basic infrastructure. Tablets and systems designed to meet the real needs of agricultural operators have been made available to them.

- Introduced the PIP approach in selected Gitega collines. The adaptability of the G50 approach to any other community-based approach for collective development made it possible to obtain better than expected results.

- Rechecked recorded cropping areas. Project beneficiaries have learned to tailor their fertilizer orders to the size of their plots. Knowing the size of their plots allows farmers to better plan ahead for their input needs.

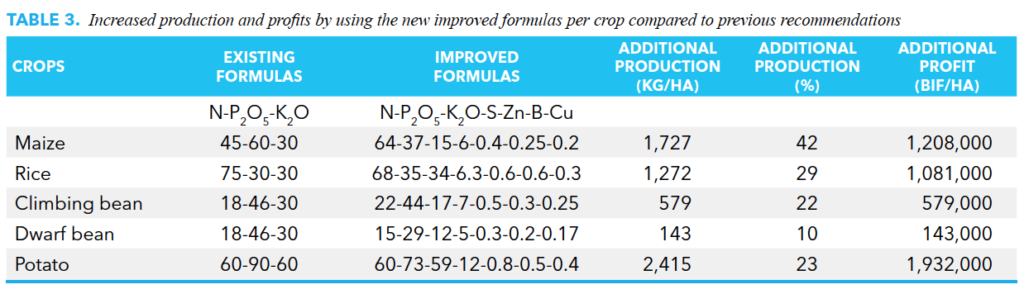

New Fertilizer Formulas and Measures to Correct Soil Acidity are Tested and Validated

To complement its efforts to promote the use of chemical fertilizers, PAPAB contributed to an experimental program on new fertilizer formulas adapted to the current fertility status of Burundian soils. These experiments were carried out within the framework of a partnership between IFDC and MINEAGRIE, especially the National Agricultural Research Institute of Burundi (Institut des Sciences Agronomiques du Burundi – ISABU) and the Soil Fertility Directorate (DFS). These experiments aimed to provide farmers with complete and more productive fertilizer formulas, incorporating major nutrients (NPK), secondary nutrients (sulfur) and micronutrients (zinc, copper and boron) that are deficient in Burundian soils. This initiative was based on the analysis of soil samples conducted in 2013 within the framework of the PAN-PNSEB project. The new soil fertilizer recommendations were not completed at the end of the PAN-PNSEB project, although the soil fertility mapping had been done. This experimental program continued within the framework of the PAPAB project to develop the final recommendations.

The first report produced in 2018 was presented and validated at a meeting held on August 14, 2018. The meeting stressed the importance of adding micronutrients to fertilizer formulas and the benefits of soil liming. Faced with the multiplicity of nutrient sources that are available on the market (sulfates and oxides, NPS fertilizers, AMIDAS, etc.), the meeting recommended trials for an in-depth study on micronutrient incorporation processes (granular method or coating). These trials should be carried out with a sufficient number of replications, since different parameters can influence the efficiency and profitability of the proposed fertilizer formulas. Moreover, the trials should extend over two additional seasons to allow better assessment of these fertilization options, even if that entails developing, within a short period, formulas that can be adapted based on these parameters. It should be possible for local fertilizer plants in the region to produce the adapted formulas to better meet the requirements of both beneficiary farmers and input dealers. It was also recommended that a scientific platform be set up to address issues related to fertilizers and soil amendments. This platform should decide on the experimental protocol for the additional seasons, even if that means expediting research findings. The proposed platform was set up with the participation of key scientists from ISABU, universities and IFDC. They met for the first time on August 24, 2018, to agree on the experimental protocol for the 2019 A and B seasons. It was then recommended that the platform be officially appointed with a specific mandate to become operational.

Following the additional trials conducted in 2019 and 2020, an updated version of the 2018 report was produced. However, a restitution session does not seem justified at this stage given the change in emphasis on the part of MINEAGRIE and FOMI with respect to the production and distribution of three new organo-mineral fertilizer formulas. However, the data from this report remain relevant and useful for the continued improvement of the new formulas, based on the research outcomes presented below and particularly those relating to additional profits and economic returns (Table 3).

Compared to the current ISABU recommendations, the new fertilizer formulas performed better and provided significant additional profits for potato, maize, rice and climbing bean. However, profit was lower for dwarf bean. For all crops, the fertilizer subsidy has reduced production costs and increased profits for farmers.

Overall, the incorporation of micronutrients into fertilizer recommendations has led to considerable increases in yields and profits for farmers. This can be built on to improve organo-mineral recommendations. Successful implementation of this fertilization option would require support from the scientific platform (IFDC-universities-ISABU-DFS), including FOMI. Meanwhile, advocacy efforts should be undertaken through the new PAGRIS project to ensure that this platform is formally established with a legal and operational framework.

Nutrient Omission Trials on Cassava

A memorandum of understanding was concluded between IFDC/PAPAB and IITA/CIALCA in August 2018 to implement joint cassava fertilizer trials. The objective of this experimental initiative was to generate a database on cassava yields, yield response to nutrients and nutrient uptake in different agroecological zones. The data collected served to calibrate decision-making tools on the use of fertilizers and soil amendments.

The two institutions were tasked with collecting data:

- IITA for leaf sampling.

- IFDC for soil sampling, measurement of morphological parameters, vulnerability scoring for pests and diseases and harvest data (yield, root quality).

The benefits of such collaboration include the synergy of actions, pooling of IFDC and IITA expertise, cost and work sharing, efficient use of resources, ease of validation and extension of the outcomes of research conducted by several partners. The Nutrient Omission Trials on Cassava is a region-wide experimental program implemented in Burundi, Rwanda and South Kivu in the Democratic Republic of Congo. In Burundi, IFDC and IITA partnered to carry out these trials which were installed in November 2018 on 45 sites in the communes of Rugombo, Buganda, Rumonge, Nyanzalac, Makamba and Kayogoro. Harvest has been completed on the experimental sites and result analysis is ongoing.

These trials have been set up again in the 2020 A season on 40 sites in Rumonge, Nyanzalac, Makamba and Kayogoro for the second replication. They will be carried out under the new PAGRIS project, through which the final results will be disseminated.

Recommendations for Soil Liming in Burundi

Trials on the dosage of dolomite based on soil pH levels were carried out in 31 communes with highly acidic soils. These trials, which started in the 2015 B season, were needed to correct soil acidity (around 30% of cultivated soils), increase fertilizer use efficiency while reducing fertilizer acidifying effect, and correct soil deficiency in calcium, magnesium and other exchangeable bases.

In 2018, a database on the results of these trials was developed and submitted for verification and approval by a commission appointed by the Minister of the Environment, Agriculture and Livestock. The database was validated and now covers 7,941 farms of 4 acres each. The statistical processing of data was under the scientific responsibility of ISABU, which has collaborated with IFDC and DFS in the design and implementation of these trials.

The results of data analysis will feed into a report on the recommendations for soil liming in Burundi based on different pH levels.

Improving the Technical and Financial Management of PNSEB

The PAPAB project provided technical support to the MINEAGRIE accounting unit in preparing for the external audit of the Common Fund for the 2014 and 2015 fiscal years. PAPAB support also included financing the feasibility study for the construction of the fertilizer plant (FOMI) commissioned by CTFA, in order to assess its effectiveness and viability in relation to PNSEB. The final report of the study (carried out in January/February 2017) highlighted the profitability of this fertilizer plant. In compliance with the memorandum of understanding between IFDC and MINEAGRIE, and a contract concluded on September 26, 2016, relating to the sharing of subsidy repayment to fertilizer dealers, 10,687,152 euros was earmarked to support PNSEB over four agricultural seasons (2016, 2017, 2018 and 2019). On instruction by the donor (EKN), the remaining 2,400,000 euros will be held in reserve for the 2021 season.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The various activities conducted within the framework of the PAPAB project with a view to consolidating the fertilizer distribution system have boosted the demand and effective use of fertilizers in Burundi. The number of households enrolled in PNSEB has considerably increased. The same applies to the volume of orders for dolomite (112%) and all types of fertilizers (69%). Support provided for the technical and financial management of PAPAB was also effective, since the project accounts have been regularly audited and the expected subsidy has been earmarked. Another significant outcome is that, based on the report of the technical feasibility study on the FOMI fertilizer plant conducted with support from PAPAB, fertilizers are now produced locally, which results in foreign exchange savings and employment opportunities with the new plant.

However, despite the subsidy, fertilizer prices have remained relatively high with no sign of slowing down as expected. The subsidy rate also remains at 30% with no signs of declining as initially expected. To boost adoption and ensure sustainability of fertilizer use, the Government of Burundi should switch to a degressive subsidy system and adjust, when necessary, to the actual situation in terms of fertilizer needs and farmers’ purchasing power.

The current system of farmer registration and fertilizer payment and distribution through PNSEB have revealed a number of flaws, as observed during the final project appraisal. This hinders wider adoption and better use of fertilizers and dolomite by farmers to improve agricultural production.

A context-specific strategy of ISFM that links soil protection, soil amendments and plant nutrition should be further discussed with farmers and agricultural trainers. This strategy should also guide FOMI in the development of suitable fertilizer formulas in the future.

Local fertilizer production has thus far been focused on food crops. This opportunity should be extended also to export crops in order to maximize foreign currency savings.

Conducting trials on the new fertilizer formulas was a time-consuming and energy-intensive process. FOMI should consider these research findings in choosing the types of fertilizers to produce rather than investing in further trials or producing fertilizers without scientifically validated technical references.

Outcomes of Component 2

Increasing Agricultural Production, Resilience, Organization of Farmers and Access to Markets

PAPAB Component 2 addresses challenges resulting from a combination of complex and interrelated factors that place farming households in a vicious cycle from which it seems impossible to escape. Aware of this situation, the PAPAB project has chosen not to provide ready-made solutions to households and communities, but rather to support them in analyzing the challenges, identifying individual and collective projects, and acquiring the knowledge necessary for their implementation. The end of the cycle can only be realized through fundamental changes in mentality, beliefs, ways of doing things and, above all, the household vision for the future. This calls for a judicious allocation of available resources for an inclusive household development in which every member takes part.

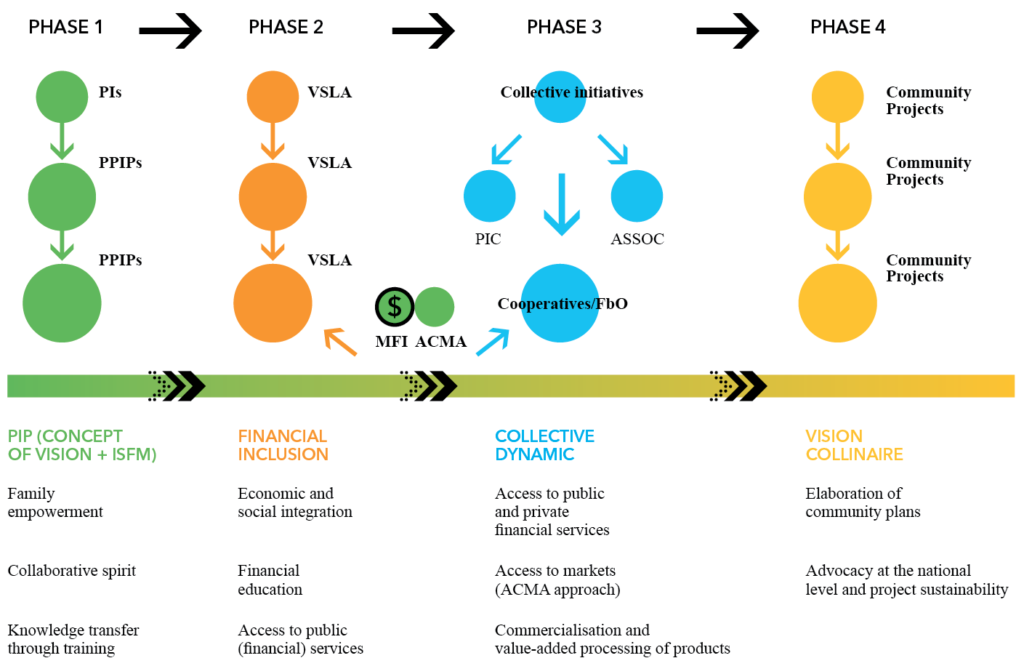

Figure 5. Diagram of PAPAB Component 2 approaches

Farmers should be convinced that protecting their farms against erosion and applying proven agricultural practices and climate-resilient techniques have proved to be an essential strategy to sustainably restore and improve soil fertility. This exercise requires that the farm vision be extended to the entire watershed to expect significant changes at the community level. Above all, farmers must be convinced that by acting alone they can achieve little, while together they can do better and more. Based on these assumptions, the PIP approach was adopted for the implementation of the PAPAB project. This particularly innovative and empowering approach fits perfectly with other technical approaches, such as ISFM; financial inclusion approaches, such as VSLA and IGG; the gender approach; vision collinaire, etc. The outcomes of Component 2 were achieved through reasoned application of these approaches and provide a strong basis that ensures ownership and sustainability of household and community projects. This was facilitated by specific structuring strategies supported by targeted communication and advocacy programs.

In the collines implementing the PIP approach, an impact assessment study highlighted, among other results, greater motivation, ownership and resilience among the project beneficiaries (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Assessment of PIP impact on PAPAB project beneficiaries

The PIP Approach as a Driver of Change and ISFM as a Priority Measure

The PIP approach has been at the core of the implementation of all activities under the PAPAB project to sustainably strengthen household resilience and improve their well-being. Initiated by the SCAD project in 2013 in Gitega Province, this approach has proven to be a technical instrument for promoting resilient agricultural systems, thereby contributing to sustainable agricultural development. Promoting this approach at community level was one of the flagship activities prior to the implementation of the whole range of activities within the framework of the PAPAB project.

Adoption of the PIP approach induces fundamental changes within individuals, households and communities. PIP farmers become agents of change. They are empowered to invest in their future and take their skills and their knowledge seriously. Therefore, PIP offers a different “narrative” compared to other similar projects and fosters motivation for action.

This approach enables visualization of the future through a plan – an achievable plan developed by the family on its own. Ownership and a shared family vision are essential to intrinsically motivate household members to act for change. PIP triggers tangible change as short-term gains are rapidly achieved due to the fact that knowledge flows quickly and people are eager to learn from others. The integration and diversification of activities ensure more resilience and sustainability. The approach stimulates collaboration and fosters cohesion within communities, as people are more united, with enhanced social capital (trust, reciprocity, networks) and more willingness to learn from one another. This leads to faster scale-up and stronger participation. In the end, PIP drives stronger commitment and creates a conducive environment for those who take responsibility, including staff and farming families, with a new state of mind, until policymakers also become fully engaged in the PIP approach.

Through the PIP approach, PAPAB has imprinted a culture of dialogue and social justice within households. The development of a PIP is based on discussions involving all family members. These discussions focus on identifying the strengths and weaknesses of the household, opportunities available to the household, priority and realistic activities constituting the household action plan, the action plan implementation time frame, role distribution, expenses involved and the origin of resources between husband and wife. This transparent debate creates a culture of dialogue and equality, particularly with regard to the division of tasks and allocation of resources. At the same time, this exercise, which household members undertake as regularly as possible, helps to address issues that are the root causes of recurring crises in many households. Women, who are usually overburdened with farm and household activities, can breathe now. Management of the scarce family resources is no longer a taboo subject or the exclusive responsibility of the head of household. In short, an atmosphere characterized by peaceful dialogue and mutual understanding prevails within the household.

The impact study carried out toward the end of the PAPAB project confirmed the huge impact of the PIP approach in the PAPAB collines. Based on data collected from 962 farmers spread over 35 collines in five provinces of Burundi, this impact study assessed the effectiveness of the PIP approach in strengthening its basic principles, namely motivation, resilience and accountability. The results of a wide range of rigorous statistical analyses show that PIP farmers are more motivated, more resilient and better stewards of their land compared to farmers who did not participate in the PIP approach. The analyses further show that the food security situation of PIP farmers is less volatile throughout the year (see Figure 2) and that they are more food secure (>20%) during the lean season compared to non-PIP farmers.

The impact study also shows that the sequential targeting strategy underlying the PIP approach (whereby farmers of the first PIP generation train farmers of the second PIP generation and so on) is inclusive and has also reached poorer farmers of later generations. According to this study, the strongest impact was observed among the innovative farmers (paysans innovants – PIs), followed by second and third generations that were trained afterward. It is interesting to note that farmers of the fourth PIP generation have seen accelerated changes in terms of motivation and, to a lesser extent, in responsibility and resilience. These are farmers from the adjacent collines who became motivated to start their own PIPs because they heard from other farmers that PIP is effective. This confirms the huge potential of the PIP approach, which needs to be further scaled up in the same PAPAB communes, but also in other provinces, with new organizations adopting the approach as their main development strategy.

Overall, this impact study has shown that the PIP approach is very effective in increasing motivation, resilience and accountability. It also recommends that the approach be further expanded wherever possible. This is obviously a great success for the PAPAB project and its partners that have become the advocates of the PIP approach, not for opportunistic reasons or objectives, but because they are convinced that this bottom-up approach delivers results. They have actually seen the evidence of its impact: collines totally transformed with more resilient cropping systems and motivated farming households that have become better stewards of their land and work together for a more sustainable future for their collines and their environment.

The PIP approach fosters the development of a vision toward a desired future and strengthens the capacities of households in all relevant technical areas. Although sustainable farming is at the core of PIP, other types of activities are integrated, including those related to health, training, agricultural product processing, appropriate equipment, improved housing and micro-credits. Emphasis is placed on knowledge transfer through farmer-to-farmer training. In line with this, within the four years of the PAPAB project, 59,575 farming households were trained (in five generations) on the PIP approach and have become “agricultural entrepreneurs” thanks to their PIPs. Additionally, 14,045 households have been trained since 2014 in the 41 collines of Muyinga, Gitega and Makamba provinces, initially under the supervision of SCAD and eventually taken over by PAPAB. In total, 73,620 households have developed and implemented their PIPs.

While PIP was initially limited to the 28 pilot collines of the six PAPAB provinces, this approach is currently implemented in 205 collines, some of which fall under the jurisdiction of provinces located outside the project area (as in the case of Rutana and Bururi).

Following the development and implementation of their PIPs, the households involved – in a second step – felt the need to scale up the approach to colline level. Therefore, communities in 49 (PAPAB) collines and 14 (SCAD) collines have collectively developed their visions collinaires. Some of the projects have already been implemented (with the communities’ own resources and/or with PAPAB support), while others are expecting external support to cover costs that are beyond the communities’ means. The projects implemented within the framework of the visions collinaires focused on access roads, water supplies, standpipes, culverts, anti-erosion ditches surrounding the watersheds, etc. A number of initiatives were supported by the communication and advocacy efforts invested by the PAPAB project to promote the use of these visions collinaires in order to feed into the Collective Community Development Plans (PCDC). By being integrated into national development policies, the PIP approach and community projects gain in ownership and sustainability, which should ensure their continuity and their extension.

When designing their desired vision and action plan, PIP households learn to structure their projects primarily around six pillars: (i) agriculture; (ii) livestock; (iii) soil protection and soil fertility restoration; (iv) income-generating activities; (v) household well-being; and (vi) training.

Although all these pillars are important and interrelated, the soil protection and soil fertility restoration pillar has been a priority in the technical and direct support provided by PAPAB. The project initially focused on training PIP farmers and other stakeholders (staff members, administrative personnel, BPEAE services, community structures), on the principles of ISFM and good erosion control practices. These trainings helped PIP farmers to better understand the importance of protecting soils against erosion and restoring their fertility in an integrated manner. In this way, PIP households could access technical and specific information, enabling them to define priority actions and select the best practices relevant to their situation to make their projects more realistic. The objective was to equip PIP households with the skills required to meet the challenge of sustainably increasing agricultural production. Raising awareness and training communities were the flagship activities of the PAPAB project.

Based on the nature of the PIPs developed, other technical trainings and experience-sharing visits were organized on request, focusing on two pillars: (i) agriculture and (ii) livestock. These trainings reinforced individual and collective initiatives undertaken by PIP households. Training areas included agroforestry and fruit tree nurseries, which have emerged gradually as the PIP approach spread in the collines (grafting techniques, use of crop protection products, nursery maintenance, etc.), as well as management techniques for innovative crops (mushrooms, beetroot, ginger, etc.) and livestock (pigs, chickens, beekeeping, etc.).

These initiatives were also supported by the PAPAB project through prize awards during “Graduation Day.” This event, closing out the different phases of promotion of the PIP approach from one generation to another, offered formidable opportunities for raising awareness on priority issues and the importance of the PIP approach. It also allowed boosting of the promotion of innovative crops through the distribution of awards in the form of improved seeds, inputs for the production of agroforestry, small equipment for the installation of anti-erosion devices, etc.

In Burundi, agriculture remains a poorly developed and low-value activity. Farmers often wait for external support as the only way out of their situation.

One day, the family of Théophile and Calinie (Colline Nyamaboko) decided to engage in the PIP approach, noticing the changes in their neighbors.

Together, they develop their Integrated Farm Plan with a vision of their farm in 3 to 5 years. This is displayed in the main room of the house as an encouragement to improve their future.

The development and implementation the IPP is guided by the key principles of the “Integrated Soil Fertility Management” approach, the first actions protect plots from erosion.

Men and women work together to implement innovative technologies and good agricultural practices, benefiting from their personal experiences as well as those of their neighbors.

Family members organize themselves together for the implementation of their PIP, in particular by making commitments on the management of family resources and income.

Through the PIP approach, Théophile and Calinie’s family sees the productivity of their farm increase progressively and sustainably, and they take justifiable pride in their own results.

The income generated is invested primarily in food, improved housing, and schooling for children.

Families engage in a process of positive, sustainable, and inclusive change.

PIP Households Organize Themselves into “Solidarity Groups for Savings and Loans” to Strengthen Their Resilience and Promote Financial Inclusion

One of the major problems facing PIP households is the lack of resources to finance their PIPs. Organizing themselves in Solidarity Groups for Savings and Loans (GSECs) allows (i) acquiring the basic notions of financial education, (ii) mobilizing savings, (iii) accessing loans for smallholder farmers, (iv) strengthening the economic power of project beneficiaries, (v) financing individual PIPs and (vi) connecting with formal financial services, while further strengthening household resilience. Based on the clear benefits linked to this type of structure, PAPAB has facilitated the creation and supported the development of GSECs through two main approaches, the Imigwi yo Gutererana no Gufatana mu nda (IGGs: Groups for Solidarity and Self-Promotion) and VSLAs (Village Savings and Loan Associations).

IGG is a step toward VSLA. With a maximum of 10 members, it is structured around mutual aid and solidarity activities. The savings collected aim at directly financing an activity previously agreed upon within the group, benefiting each member of the group in turn. These groups are also organized to jointly carry out mutual aid activities such as “Ikibiri” (organization of field work in groups).

VSLAs are made up of 25-30 members, mainly structured around savings and loans issues. These associations operate in line with a well-established process introduced by CARE, a non-governmental organization initiator of that approach based on a 12-month cycle. VSLAs have a more structured format, with a double-entry bookkeeping system (debits and credits), integration of the concept of interest rate recovered at the end of the cycle and application of operating rules and procedures for group activities and meetings.

This is an important step toward organizing farming households around more structured activities, which forms the third line of operations of PAPAB Component 2. With the GSECs, farming households realize the possibilities and benefits of getting organized to develop activities together. These activities strengthen social ties within communities by creating spaces where people can meet, exchange and share. They can also reflect on issues of interest to them and define relevant activities as an essential basis for getting organized to develop community projects.

GSECs have boosted self-development dynamics mainly through:

(a) Access to finance: The VSLA approach has enabled members to access financing for: (i) leasing of farming land; (ii) housing improvement; (iii) loan repayment; (iv) children’s education; (v) purchasing food; (vi) health care; (vii) raising small livestock; and (viii) improved nutrition.

(b) Achievement of objectives: Implementation of VSLAs has made it easier to: (i) meet the needs and achieve the objectives of VSLA family members; (ii) increase household development (contributing to covering some family needs); (iii) promote AGRs through the VSLA credit scheme; and (iv) assist PIP household members in implementing their PIPs.

(c) Economic power: The VSLA approach made it possible to: (i) improve household income thanks to properly constituted savings; (ii) make investments thanks to VSLA credit; (iii) reduce poverty levels in VSLA member households thanks to VSLA credit; and (iv) eliminate the loan-sharking phenomenon (umurwazo) in VSLA member households.

(d) Access to public and private services: Implementation of VSLAs enabled participating members to: (i) access a health insurance card (CAM) thanks to VSLA credit scheme; and (ii) ensure the schooling of their children.

(e) Financial education: VSLA members confirm that the approach provided them with access to a portal for learning about savings and loans, a culture of savings, and financial education.

(f) Economic and social integration: The VSLA approach proved to be very relevant as it has contributed to: (i) strengthening social cohesion within households; (ii) alleviating, through VSLA loans, the stigmatization of women and poorer households who could not afford to buy uniforms and other school materials for their children; (iii) organizing mutual aid; and (iii) facilitating access to a productive collective workforce.[5]

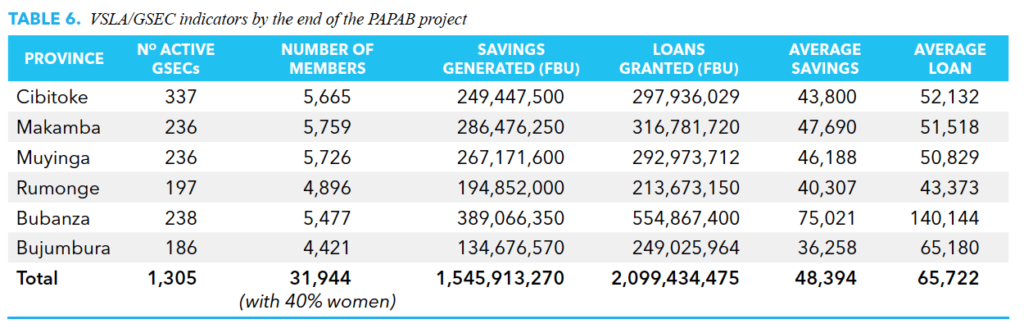

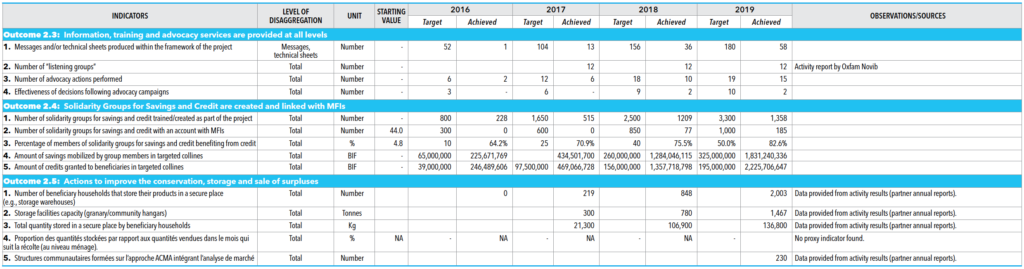

At the end of the four years of the project, the outcomes of the GSECs can be summarized as shown in Table 6.

Structuring PIP Households into PICs and Cooperatives

Within the framework of the PAPAB project, the PIP approach has greatly opened up people’s minds. Long hidden ambitions have emerged. There were many farmers who wanted to invest in their activities but their initiatives were blocked as they found themselves trapped in the vicious cycle described previously. With PIPs and GSECs, they have come to realize that little can be achieved by acting alone. They understand that, by combining their ideas and resources, they can increase their income and raise sufficient capital to invest while sharing and limiting risks. Thus, many joint initiatives have emerged within the communities, with very different forms and various objectives. Some initiatives were intended to respond quickly to a need and at a given time (agroforestry nurseries, organization of grouped purchases, etc.) and therefore did not evolve over time. Other initiatives intended to develop longer-term activities and were gradually organized and structured.

The vision collinaire also contributed significantly to the development of community projects and the structuring of households for their implementation. Regarding the best forms of organization, it appeared that cooperative organizations and PIPs are favored by PAPAB beneficiaries. Depending on their dynamism and their specificities, these forms of organization have received technical and direct support from the project, mainly to acquire the necessary knowledge and skills to develop and professionalize their activities. Once formally recognized and functional, the most dynamic cooperatives and corporate structures have also benefited from financial support contributing to the procurement of appropriate equipment and infrastructure. These contributions were made according to established principles, always with a view to fostering self-reliance and empowerment of recipient organizations on a consistent basis.

The vast majority of cooperatives were formed around storage infrastructure built with financial support from the project. Most of them are focused on agricultural produce conservation, marketing and processing. They generally have a large number of enrolled members who have voluntarily subscribed to shares in the share capital of their cooperatives. In contrast, PICs are small structures with varied activities and whose membership usually varies between five and 10. These PICs essentially grew out of the IGGs and VSLAs. They were built around income-generating activities:

- Control product supply (timing, volume and quality) and associated production costs.

- Organize themselves to improve their bargaining power and collectively meet commitments to buyers and sell more.

- Ensure better prices and increased income by reducing production costs.

In addition, in collaboration with the MFIs active in PAPAB action areas, trainings on the warehouse receipt system were provided in the six provinces covered. The objective of these trainings was to help FBO members understand the warehouse receipt mechanism, which gives farmers the possibility to access agricultural credit to finance their activities and to delay the sale of their harvests while awaiting better market opportunities and more profitable prices. The series of trainings on the promotion of the ACMA approach was completed by the training of agribusiness cluster (PEA) members on the establishment of communal consultation frameworks and by the coaching of 40 cooperatives on the development of bankable business plans. This coaching program allowed representatives of each of these cooperatives to specify their activities and operating mode, their current level of achievements, problems encountered, and objectives and strategies they will implement to position themselves on the market. This helped them prepare for developing their business plans to obtain bank loans, achieve their project objectives and establish themselves on the local market.

The training was provided to 230 representatives of FBOs and various PEA stakeholders, allowing them to gain a grasp on:

- Multi-stakeholder approach in the development of PEAs.

- Calculation of production costs, market analysis and marketing strategies.

- Different relationships between PEA stakeholders.

- Need to create horizontal and vertical synergies between PEA stakeholders at the local level.

- Establishment of communal consultation frameworks.

A Communication Strategy based on Project Targets and Approaches

The PAPAB project achievements are partly related to the communication strategy and tools developed for information dissemination and knowledge transfer within the framework of the project. The preferred knowledge transfer mode was through trainings, supplemented and reinforced by experience-sharing visits (testimonies). Since the PAPAB technical package was conveyed through the PIP approach, the adult training technique (farmer-to-farmer) was the main channel for disseminating knowledge. The practical nature of the PIP approach and its relevance to the problems of the rural environment facilitated its adoption by project staff and target populations. The project also used interactive communication tools, particularly exchange platforms such as workshops for results sharing. Specific communication tools have been developed, including sketches, slogans, films and videos on project-related topics. An annual newsletter reporting on PAPAB achievements was regularly published. Overall, these tools contributed to increasing awareness of the PAPAB project and, particularly, the PIP approach.

Farmers’ Forum and Agricultural Products Fair, 2018 edition, Bujumbura (September).

Through these information and communication channels, PAPAB has strengthened project activities relating to strategic thematic areas, namely soil fertility, self-promotion principles (dialogue, planning, PIP + PIC, etc.), access to inputs (seeds, fertilizers, lime, etc.), developing agriculture that is integrated, resilient and tolerant to climate change, advancing innovative approaches, community dynamics and the benefits of working in associations/cooperatives, the vision collinaire and women’s empowerment. PAPAB has fostered a greater awareness of these issues through the organization of exchange workshops between project stakeholders and beneficiaries at all levels, in collaboration with the different committees established by the stakeholders themselves (vision collinaire committees, cooperative committees, gender monitoring committees, etc.).

Always with a view to supporting self-promotion of farming households, the project has strengthened the capacities of beneficiaries on advocacy and lobbying techniques so that they are able to bring their concerns to influential actors capable of solving problems facing their communities. The project has also facilitated the choice of opportunities or allies who could support farming households in taking their voices to decision-makers. This was made possible through their participation in various events such as the Farmers’ Forum and agricultural fairs (FOPABU), International Women’s Day and International Day of the Tree.

Communication and advocacy efforts were carried out in tandem. Appropriate communication channels were used to disseminate information and advocacy messages that beneficiaries were able, in turn, to use to reach a general public, and also decision-makers at all levels:

- 63 product messages and technical data sheets were produced during the life of the project, including one in 2016, 12 in 2017, 23 in 2018, 22 in 2019 and five in 2020.

- 15 advocacy activities, including exchange forums, were aimed at influencing stakeholders to apply the PIP approach in their programs. Through special radio broadcasts, stakeholders were invited to debate and encourage decision-makers to respond to the needs of project beneficiaries, particularly women.

- Two major decisions were made as a result of these advocacy efforts:

- Decision 1: In the minutes of the 2018 National Agricultural Fair and Forum that took place September 4-7, 2018, it was recommended that each farmer should work with a vision and a plan of household activities. The purpose of PAPAB participation in the National Agricultural Fair and Forum was to influence government and non-government stakeholders to take ownership of the PIP approach and encourage farmers to adopt this approach during the panel debates, which made up the largest part of the program. Innovative farmers had a golden opportunity to demonstrate and explain the benefits of the PIP approach in supporting sustainable agricultural development at the household level. Participants in the panel debates have shown a keen interest in the National Agricultural Fair and Forum and in the PIP approach. The PAPAB stand was very well attended; although there were no agricultural products to buy, PIP drawings and other communication material explaining the PIP approach were available.

- Decision 2: A panel workshop took place in the Bubanza commune on December 20, 2018, bringing together project stakeholders, decision-makers and beneficiaries to promote the implementation of the visions collinaires in Gatura and Mugimbu collines. This workshop also aimed at influencing the development of visions collinaires in other collines outside PAPAB’s area of operation.

Materials on PIP

PIP Brochure

PIP Manual

How the PIP Approach Changes People

How the PIP Approach Changes Farmer Households

How the PIP Approach Changes Farms

How the PIP Approach Changes Communities

How the PIP Approach Changes Institutions

Videos

Techniques to Teach the PIP Mboniyongana Approach

Soil Fertilization: A Need in Burundi

PIP Mboniyongana – The Dawn of Development

The Ownership of PIP ACMA Leads to Development

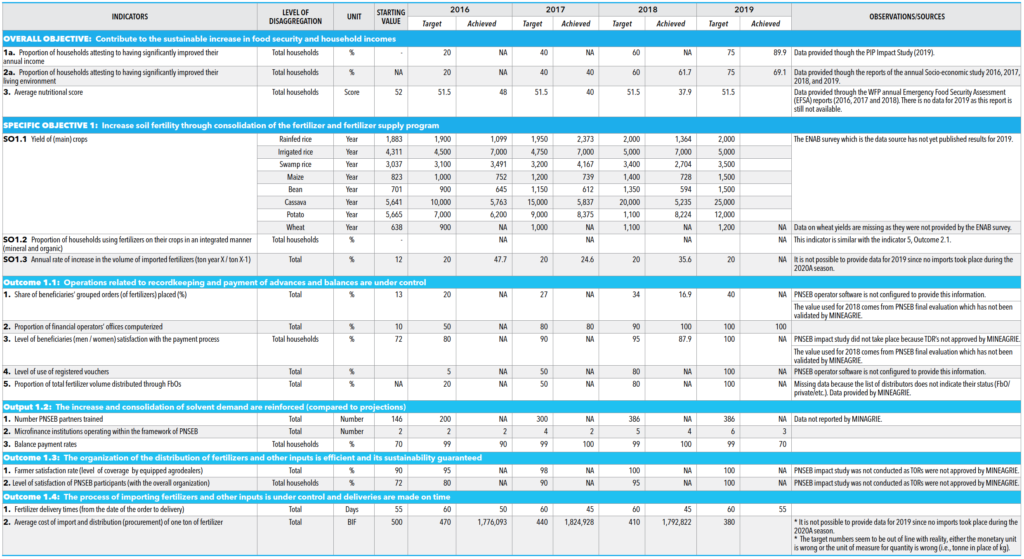

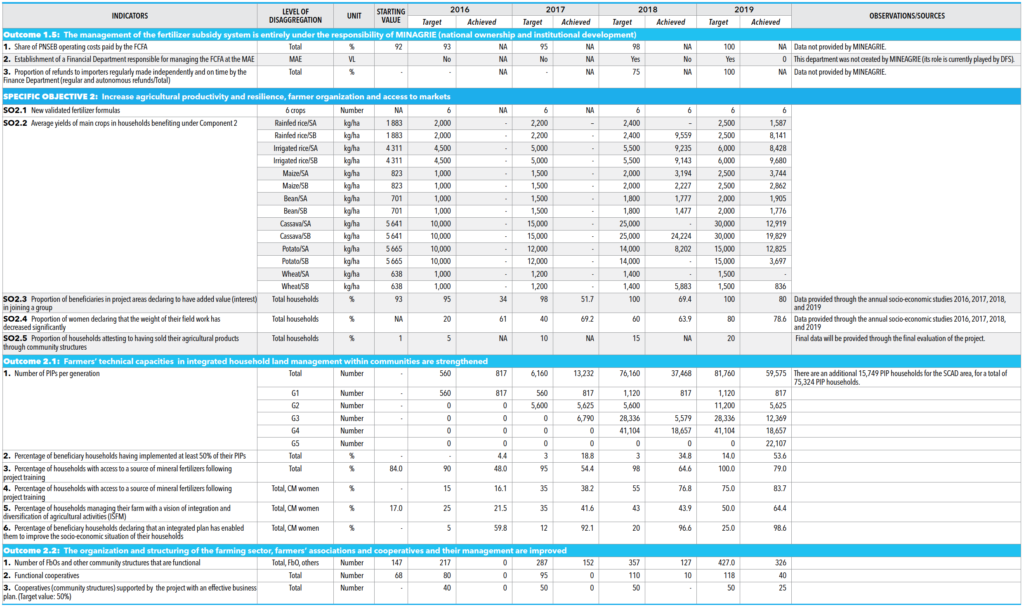

Based on the monitoring and evaluation data and the results of the evaluation studies, the PAPAB project has been largely beneficial for its target population and its objectives have been largely achieved, as shown in the Monitoring and Evaluation Matrix in Annex 1 of this report.

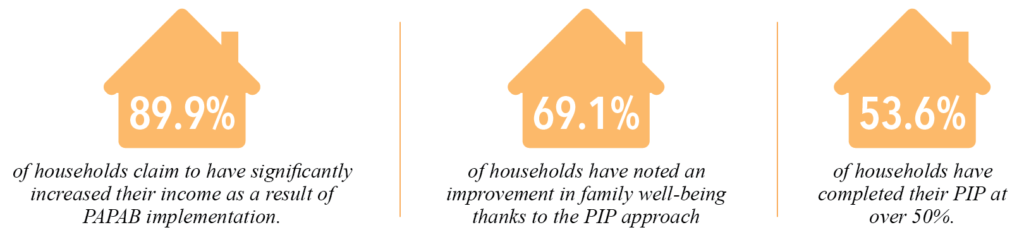

Regarding the project’s overall objective, the outcome indicators established for monitoring and evaluation purposes were: (i) the proportion of beneficiary households attesting that they have increased their agricultural income with the project and (2) the proportion of households attesting that their family well-being has increased by 20% or more compared to the situation before the project. Based on the data recorded, the project achievement levels were 89.9% and 69.1%, respectively.

These high performance levels recorded with the PAPAB project are largely due to the expertise and dynamism of the actors and organizations involved in its implementation but, above all, to the originality of the PIP approach that served as the backbone of the PAPAB project.

The logic of self-empowerment and self-promotion integrating the reality of the household from its various angles, as well as the project realistic ambitions, has catalyzed a remarkable rhythm to the changes that can be observed in the lives of the beneficiary communities.

The development of integrated farm management activities (soil fertility improvement, erosion control, use of improved seeds, etc.), combined with better access to fertilizers for farmers through PNSEB, has significantly contributed to the achievement of spectacular production levels (see the Monitoring and Evaluation Matrix in Annex 1 of this report).

Overall, PAPAB is a project that can be characterized as innovative, rich, relevant, and ambitious.

Beneficiary farming households that developed their PIPs were faced with the challenge of their implementation. VSLAs provided them with unparalleled support in financing the implementation of their PIPs. These households have come to realize that they can rely on their own resources and on the opportunities existing in their environment to carry out their own projects.

The PIP approach has radically changed the mentality of individuals who have moved from a recurring wait-and-see attitude induced by the gratuities of previous projects to greater awareness and self-commitment. As a result, PIP households have been the first to take the lead in managing their own development as they became aware that any external support would only come as opportunities to complement or support their actions already undertaken. This change in mentality has materialized in concrete actions, particularly those related to integrated land management that have yielded significant increases in agricultural production and encouraged the grouping of project beneficiaries into various associations and cooperatives (FBOs, PICs, VSLAs). Within the framework of the PAPAB project, the PIP approach has already proven its worth in terms of sustainable development of farming households and communities.

Beyond the individual initiatives of households, the promotion of the vision collinaire is a fundamental step toward the integral and integrated development of colline communities. In the collines where already developed and implemented, the vision collinaire has brought to light the great capacity and potential of communities to manage their own development once they are made aware of the challenges with guidance from motivated and enlightened leaders.

An obvious fact is that setting up the foundation for a change in mentality to move forward in the effective implementation of project activities, with intrinsically motivated farmers, is a lengthy process. Moreover, the management of the project by a consortium entails specific requirements, such as the need for a common understanding before concrete actions are undertaken, which weighed heavily on the implementation schedule in the field. However, the benefits derived from this type of management largely offset the time spent in strategic meetings.

The grassroots approach, the credibility of partner organizations and a good grasp of the local and field context played a major role in achieving the project results as recorded in this end-of-project report. The relevance of the message is not sufficient in itself; a trustworthy messenger is crucial. PAPAB has deeply and positively impacted its area of operation by enhancing intra- and inter-household cohesion, increasing awareness, and fostering smart planning and management of agricultural activities. All of this has led to considerable improvements in soil fertility and crop yields.

PAPAB is an innovative project that has dared to invest in new approaches while adopting and strengthening existing and complementary approaches. This has set the stage for a more coherent overall impact. Indeed, Component 2 is an interesting combination of several approaches, such as PIP, ISFM, GALS, VSLA, the structuring of farmer organizations and the development of visions collinaires. The project has also developed new relational dynamics, including inviting couples to jointly participate in the initial training courses on PIP and ISFM. This greatly facilitated ownership and commitment by PIP household members, ensuring a real household approach in which all members are empowered to fully participate in project design and implementation.

PAPAB is a rich project in the diversity of topics and issues covered, but also in the diversity of actors and stakeholders directly and indirectly involved in the implementation of the project, who have all contributed their specific expertise.

PAPAB is a relevant project since its objectives are aligned with the needs of its target populations and communities.

Finally, PAPAB is an ambitious project. By focusing on a self-promotion approach that calls for a change in mentality and intrinsic motivation of farmers, the project itself is part of a long-term vision. This is a commendable and ambitious initiative given the current situation of Burundi. However, the dynamics set in motion need to be strengthened in the future through sustained support from other sources. Additional actions are required to strengthen the dynamics launched in the initial collines, while new initiatives should be developed to support the extension of the geographical coverage of the project approach. It is also imperative to foster ownership by other stakeholders and public institutions in an effort to avoid competitive situations, or even incompatibility of approaches in the field, and within the same communities.

Annex 1: Monitoring and Evaluation Matrix of the PAPAB Project

Annex 2: PAPAB Testimonies from PIP Farmers

Eric Ntiranyibagira

“The truth is that in the household, without a good relationship that allows for open dialogue, joint planning, task sharing and good resource management, nothing works. At home, before PIP, there was no dialogue, neither planning nor sharing of household activities. I used to spend my time at the bar with my friends even with no money. To tell the truth, I was a thief in my own house; sometimes I would secretly take part of the harvest and sell it at a ridiculously low price just to have money for drinks. I would sell and buy household goods without first consulting my wife.

“For example, one day I sold my bike, without telling my wife, to pay off debts related to drinks shared with my friends. I also very much regret having bought a plot of land without even informing her, and she got to know about it afterwards, through our neighbors. With her advice, I could have found a plot with a richer soil compared to the one I bought, which required a lot of money as investment to restore its fertility. Production in our household was low due to the fact that my wife was working alone on the farm and also due to poor knowledge of agricultural techniques, the use of undeveloped soils, the use of unimproved seeds and the non-use of fertilizers. Disputes that prompted me to even beat my wife were too frequent before I realized that I was the true cause of all these evils.

“In Mparambo II, changes could be observed by everyone in the farms of the first beneficiaries of Mboniyongana PIP. We, in turn, have also attended the trainings provided under the supervision of the PIS of our locality. These trainings have impressed me a lot and I decided to discuss this with my wife. We went step by step until we developed our own PIP. Then, I tried to convince her that the PIP trainings had really changed me and that we could join forces to implement our PIP. Before, my wife was reluctant to join any association, but as she saw that I had started participating in farm activities and could give good suggestions for the development of our household, she accepted. Indeed, her acceptance was related to the concrete actions I had carried out and my new improved behavior.

“From there, based on our planning, we identify the monthly, seasonal and weekly priorities to discuss, and we exchange on strategies and means to implement our PIP. Dialogue within our family has become a routine practice, particularly in the evening while waiting for the food to be ready. So, dispute times have been replaced by opportunities for fruitful exchange and joyful family reunion that make the children feel good and let them voice their opinions. All this was the result of a climate of trust that gradually grew within the family as I was able to fulfill my mission as head of the household.

“With the restoration of this climate of trust, people in the neighborhood began to notice that our household was well organized. This explains the different responsibilities given to my wife and/or to me. For example, my wife is the treasurer in her VSLA group. Six households that were experiencing marital conflicts came to us to help them solve their problems. Among them, a couple wanted to divorce, but today, they are here with us, they are fine and together and they have joined the VSLA savings and credit group.”

ESPÉRANCE NIMPAYE

“Any project to be carried out within the household is discussed within the family. I applied for a loan of 100,000 francs from the savings and loan group and bought tiles to improve our home. When I applied for this loan from the VSLA, they asked me to bring my husband to make sure that the repayment will be made. My husband was very happy that I took this step. He reimbursed 50,000 francs and I repaid the rest. When my husband saw how I was applying what I had learned, he got interested. He also noticed that I had changed completely. Before, there was not any possibility for me to apply for a loan, so he was even more impressed. Then, he decided to learn the PIP approach.

“Now, when my husband earns some money, he comes home and we discuss how the money will be spent. My neighbors come to me seeking advice. I make them understand that when a woman does not contribute to the family income, it’s the beginning of poor collaboration. When your spouse sees that you contribute to the development of the family, you are valued. So I told them what I’ve learned with the PIP approach. I explained how the VSLA works and they too decided to go and apply to become VSLA members.

“Following the trainings on the PIP approach, I first started sharing what I had learned with my husband. Then we would sit down together to agree on the working schedule. We managed to transform our traditional agriculture into a modern agriculture. Row planting, contour farming, observing the agricultural calendar, these were the first activities that we initiated. Within our household, we have planned for our future; this includes improving our home, buying a cow and purchasing a farming plot. When we want to undertake a project, we sit down together and make decisions together. This is because dialogue within the family has improved. For example, we’ve bought three goats: my husband contributed with an amount of 100,000 francs Bu and I gave 50,000 francs. Within our community two neighboring women came to me for advice on how to settle disputes with their husbands. I advised them accordingly, and today these women can testify that their households are at peace thanks to my advice.”

3 Avenue Bweru, 1995 Bujumbura, Rohero II – BURUNDI

+257 22 257875

Footnotes (Click the footnote number to return to your last location)